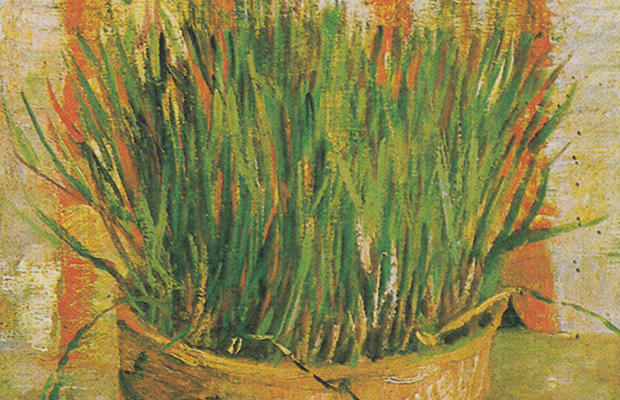

Lemongrass

Why did Vincent van Gogh paint this pot of straggling grass-like leaves? At first I mistook them for lemongrass, the third in our selection of plants that give us citrus aromas without the acidity of the fruit.

Lemongrass is used in south-east Asian cooking to get a pleasant, slightly fusty lemon flavour, using fresh stems either finely chopped or cut into inch lengths and bashed to release the scented oils; we enjoy it in Thai and Indonesian cooking.

My fellow columnist Kate Poland tells me that lemongrass is possible to grow here in London, even outdoors if in a sheltered area. As tropical plants, they can’t stand frost so Kate’s advice is to keep them in pots which you can bring indoors if it gets very cold. But keep them in a sunny position.

The possibility that Vincent knew lemongrass as an import from Indonesia, or perhaps in Paris as a part of Vietnamese cooking, is tempting, but unlikely. The surge of post-liberation Indonesian cooking came about after the Second World War in Holland and flourished in towns like The Hague. Here, ex-pat citizens longed for authentic food rather than the much-loved hybrid rijsttafel – at its best, a delicious array of dishes from all over Indonesia, served with mounds of rice, but sometimes a bit stodgy.

It’s in the back streets of S’Gravenhage (unpronouncable alternative name for Den Haag, The Hague), that genuine Indonesian cuisine still flourishes.

Pronunciation could once be fatal. The German occupation of Holland was brutal, and when it was defeated, those remaining soldiers who had not got out in time pretended to be Dutch. ‘Dutch are you? Then let’s see how you pronounce Scheveningen?’ If he got it wrong, they shot him.

The unique combination of guteral ‘g’ and ‘gh’ (like ‘ch’ in ‘loch’, and the ineffable ‘sch’ ) in the name of this seaside extension of the Hague, gives us difficulties too, so Van Gogh gets softened to Van (as in white van) Goff (as in bad cough). Instead, let’s call him Vincent.

A closer look at his plant pot shows the flattened leaves of garlic chives that we can buy in many of Hackney’s Asian supermarkets, stashed away in the chilled display cabinets alongside other green plants and herbs, basil and mint of various kinds.

This mild tasting version of chives can be chopped small to season a dish just before serving, or cut into inch lengths as part of a stir-fry. But there is no clue as to why Vincent painted them, with the background of an oriental textile, using orange hues to emphasise the greens and browns of the chives. He implements the carefully considered colour theories of Newton, Goethe and Wittgenstein, baffling to this column but essential to Vincent, aspiring to go beyond his Impressionist friends to figure out how to convey sensations of colour with paint.

The swift thin brushstrokes he was experimenting with in the 1870s were ideally suited to portray this plant and its fibrous root system, so different to the sturdy stems of lemongrass, is clearly shown in the bottom right corner.

Yellow was a colour cherished by Vincent – he painted his house yellow and wallowed in the golden cornfields and hot skies. And even though he claimed to have little or no interest in food, finding plain bread quite satisfactory, he must have enjoyed the bright sight of a hearty bouillabaisse flavoured with saffron, or mounds of fragrant cous-cous or polenta, or even the yolks of a simple oeufs sur plat cooked at home by his bossy friend Gaugin.