‘The spirit of a place’ – How Dalston painters and potters fought back to save studio block from closure

Painter Ansel Krut in his studio. Photograph: Josef Steen / LDRS

An artists’ and creative studio space in Dalston has celebrated its grand re-opening after being brought back from the brink earlier this year.

Hackney Council had moved to sell-off the hub Ashwin Street in the heart of Dalston’s ‘creative quarter’, having flagged that the Victorian-era building was crumbling into “dangerous disrepair” and deeming it too expensive to maintain.

Fearful of a private sector “carve-up“, V22, which runs artists’ workspaces in Hackney, sought help from the Greater London Authority (GLA), and in June bought the studio block from the Town Hall at the market price of £1 million.

The new arts centre was unveiled on Tuesday morning (16 September). Photograph: GLA / James O Jenkins

As they welcomed the community, along with Hackney’s mayor and London’s deputy mayor for culture and creative industries to the launch of the new ‘Ashwin Art Centre’ on Tuesday (16 September), artists who have relied on the space for years “breathed a sigh of relief” as Caroline Woodley confirmed it would be a permanent site for creative studios.

‘Most artists are chased out’

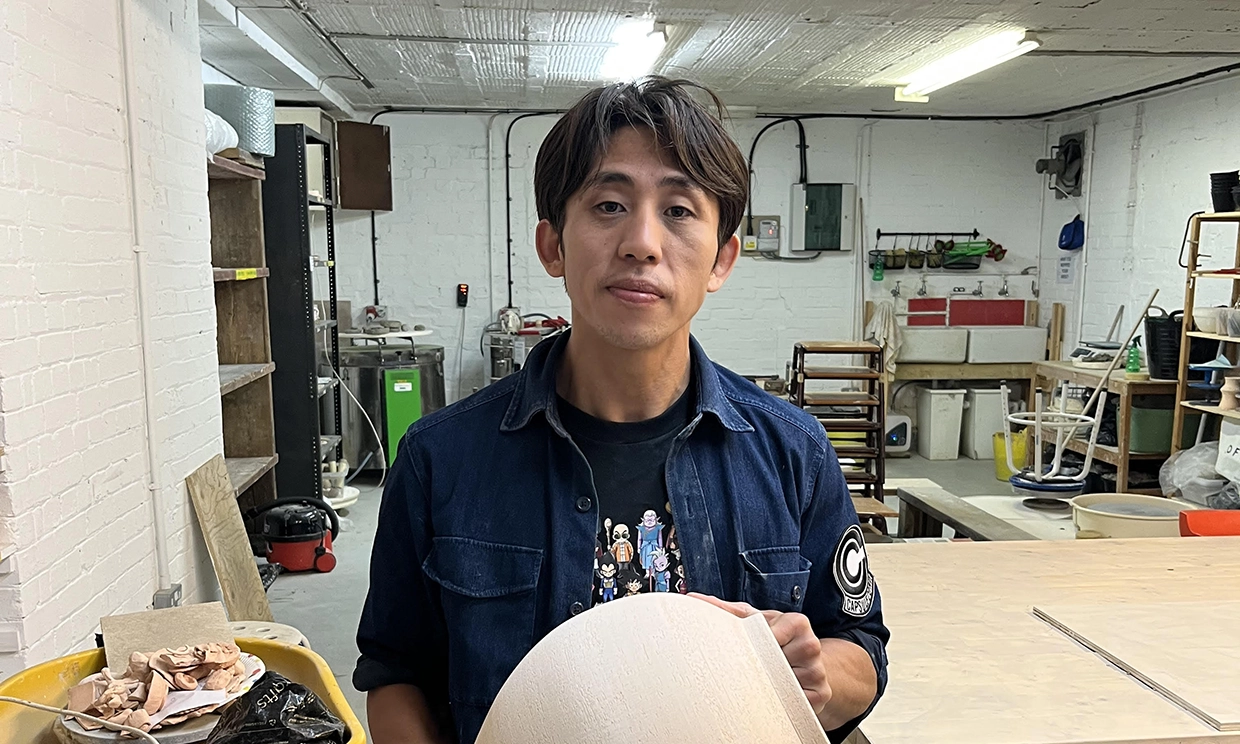

Ceramics artist Nam Tran, who runs his pottery studio ‘Cernamics’ from Ashwin Street, said this meant an end to his days as a “pottery nomad”.

He said: “This is our fifth or sixth studio,” explaining that constantly moving around was par for the course for London’s artistic community.

“A lot of studios open and close because of rent. We used to be at the Biscuit Factory in Bermondsey, but everyone was kicked out when it was shut and re-made into high-rise apartments.”

Ceramicist Nam Tran in his pottery studio. Photograph: Josef Steen / LDRS

With this new stability, Cernamics can focus on “exciting” future projects and carry on offering pottery classes for primary school children several days a week. “Parents just love bringing their kids in,” he added.

Royal College of Art alumni and painter Ansel Krut has been based at Ashwin Street for 17 years.

He said the usual story for artists like him is being “chased out of studios into places nobody else wants” and considers himself lucky to have survived in his field for four decades.

“It’s ridiculous isn’t it? Studio is so central to any artistic life, but if you want to be – or have to be – in London, it’s almost impossible to find a studio and it’s becoming even harder,” he said.

“Now I can have this studio for as long as I need it, but it’s an unusual and privileged situation. It shouldn’t be, but that’s the reality. I’m incredibly lucky and I can’t believe it.”

‘Part of our human rights’

Painters Fidji Lapios and Kaja Stumpf pay £530 a month to share a studio in the block, which they say is much more affordable than other spaces in London.

“[V22] haven’t raised the rent beyond inflation and they prioritise local artists, which is really important. There are quite a few more mothers in the building and kids are running around,” Fidji said.

Theatre-maker and performer Anna Birch, a Dalston local since the 1980s, has also been able to expand her “community-oriented, feminist” practice by sharing her space overlooking the neighbouring Dalston Eastern Curve Garden.

Painters Kaja Stumpf (L) and Fidji Lapios (R) pay £530 a month to share an Ashwin Street studio in the block, which they say is much more affordable than other spaces in London. Photograph: Josef Steen / LDRS

“When we heard the studios might be finishing we were all really shocked. Rents in London are so high that you need somewhere affordable to keep things going,” she said.

“Everybody here believes that creativity, community and culture are key to social cohesion and wellbeing. It’s part of our human rights that we have these artist communities.”

Ms Birch added she especially wanted to stay in the ‘creative quarter’ because of its opportunity for collaboration with other nearby organisations including the avant-garde music venue Café OTO and the Arcola Theatre next door.

‘We kept on fighting’

When the Town Hall announced plans to sell-off Ashwin Street, V22’s CEO Eran Zucker and others dreaded the prospect of private developers swooping in, hiking the rent or evicting them to bulldoze the building and make way for expensive flats.

“The margins on affordable studios like these don’t allow us to lose a building. We’d have had to either scale down or shut down,” he said.

But time was on the studio’s side, as the council was able to apply to make the area a ‘Creative Enterprise Zone’ under City Hall’s new planning rules.

Eran approached the GLA, which worked closely with them to see the sale go through. “Their support helped us keep on fighting,” he said.

Once it had secured the area’s status as one of these zones, the council made it a condition of sale that any buyer guaranteed a certain level of affordable artist studio space “in perpetuity”.

‘Regeneration, not gentrification’

London’s deputy mayor for culture and creative industries Justine Simons said this formed part of the GLA’s ambition to “hardwire creative studios into the city” and stop artist communities from being pushed out.

Harking back to her days at art school, Hackney’s mayor Caroline Woodley said she knew firsthand the story of “gentrification not regeneration”.

L-R: V22 director Edward Benyon, Hackney mayor Caroline Woodley, 216 Signs’ Joe Harrison, London’s deputy mayor for culture and creative industries Justine Simons, and Hackney South MP Meg Hillier. Photograph: GLA James O Jenkins

As for the crumbling block itself, one of V22’s directors Edward Benyon said that while it needed a new roof and a fresh lick of paint, there would be “very little” change to the building.

Speaking in his top-floor studio, Ansel added that for many, especially those focused on monetary value, the impact of artistic hubs like Ashwin Street were “hard to pin down”.

He added: “Often, it’s not tangible, because what it brings is the spirit of a place.”