‘Art for the people’: How Dalston’s enduring peace mural captured a community

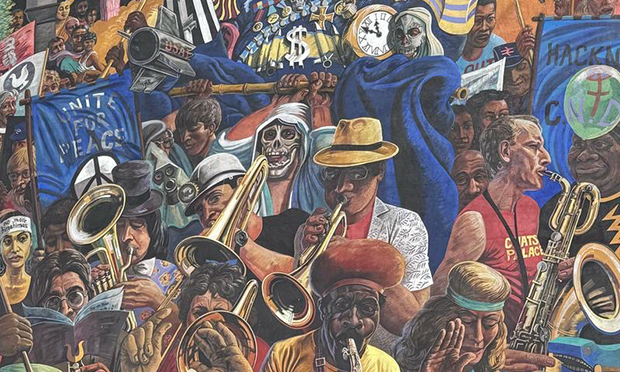

Part of the Hackney Peace Carnival Mural. Photograph: Josef Steen

What do brass instruments, skeleton masks, and ticking clocks have in common? At first glance, the mural overlooking Dalston East Curve Garden is a bold, kaleidoscopic ode to life – with no rhyme or reason required.

Portraying a peace parade, here are saxophonists and trombonists blasting with fervour, peaceniks waving their rippling banners, and women in colourful headwraps holding their hands aloft in ecstatic pride, submitting to the glory of the moment.

But look a little longer and the piece’s surreal solemnity, nestled in the cornucopia, starts to emerge. Amid a sea of plaintive faces, a slight-looking Asian woman’s headband reads ‘No More Hiroshimas’. An artillery shell, draped in the Soviet flag, hurtles towards what appears to be a gargoyle shark. A bespectacled musician presses his spindly yet swollen, red-marbled fingers on the brass keys, half of his chalky face buried in a newspaper. Perhaps to understand his times, or maybe just to seek refuge in the bulletins.

On 17 May, residents packed the Hackney Archives to hear the mural’s story, in one of several Hackney History Festival (HHF) events. Commissioned by the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1983 amid escalating cold war tensions and the rise of anti-nuclear movements, the Hackney Peace Carnival Mural was designed by artist Ray Walker. His son Roland joined the HHF’s panel to help chew over its vibrant, progressive origins and legacy.

An alumnus of the Royal College of Art (RCA), Ray Walker’s tough upbringing in Toxteth, Liverpool, led him to painting in order to escape his “drab environment”, Roland says.

As part of a Merseyside rock and roll band The Flintstones, Ray also warmed up the Cavern Club stage ahead of the Fab Four. He used the cash to fund his time at art college, first in Liverpool and then the RCA in 1966.

By the sixties’ end, Walker had come to London with a penchant for oil painting. Living on Beck Road with his wife, Anna, his visions were typically on a huge scale, blending both fantasy and social realism. The former influence is unmistakably from the godfathers of the Mexican mural movement, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, but there are also flashes of German Expressionism, Roland says.

“He was really trying to get out of this sort of formalistic gallery mentality. Though he’d had some success in that field, for him this was not what art was about. He wanted it to be for the people.”

Walker’s canvases were London’s decaying streets, often littered with rubbish and vermin. He sought to enliven the city’s “forgotten areas”, Roland says, implying the same instinct that led him to paint in the first place was now colouring the washed-out quarters of the capital.

Embracing this work outside the exhibition halls, Walker based his designs and inspirations on community-based projects. He later joined the collective London Muralists for Peace (LMP) alongside Brian Barnes, Paul Butler, Dale McCrae, Pauline Harding, Carol Kenna and Stephen Lobb, who composed four other ‘peace’ artworks across the capital.

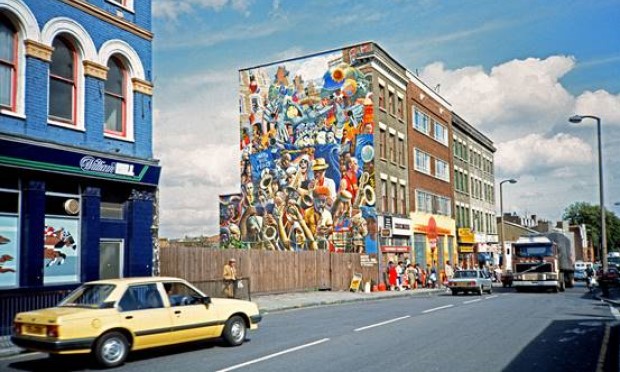

The peace mural, pictured in 1985. Photograph: Alan Denney

While Dalstonites might be protective of the precious mural overhanging the Curve Garden’s small plaza, Lambeth, Westminster, Greenwich and Lewisham also had their own.

Authorised by the GLC’s Tony Banks, later one of Tony Blair’s ministers for culture, only two artworks remain, the others preserved by old photos. Still standing is Riders of the Apocalypse in New Cross. Another one of Walker’s murals on Cable Street, depicting the notorious battle against Oswald Mosley’s fascists, also endures. Without “constant care”, says Roland, the murals are prone to deterioration, notwithstanding the whims of redevelopment.

Walker stamped his progressivism over other “politically-charged” pieces, including one at Brick Lane’s now-demolished Chicksand Estate, with a British bulldog encapsulating nationalist rage against the city’s “downtrodden” Pakistani and Bangladeshis migrants in the form of a tiger.

Peace Carnival’s themes are no less overt, fanning causes like ‘Jobs Not Bombs’ and the miners’ strike. But here they seem to be the second order of business, obscured by the flames of communal fiesta burning beneath a deep blue sky.

At its heart is the bustling band, portraying local performers affiliated with Chats Palace Arkestra, including the angular Alan May, clad in his sleeveless band tee, the Jamaican-born Jah Globe, and Panama hat-wearing Stephen Murray.

May admits one liberty: “I didn’t bring the saxophone.”

The preliminary drawings themselves were based on a real parade through Hackney’s streets, which May recalls starting near the Town Hall. Some have identified the Victorian-era Navarino Mansions at its edges, according to panellist and local history buff Laurie Elks. But the Dalston mural was never gazed upon by Walker, who died of a heart attack aged 39 in 1984. His widow, Anna, completed the mural in his name (she is visible in the work’s bottom-right-hand corner), with the help of friend and fellow artist Mick Jones.

This year, which would have marked Walker’s 80th birthday, sees his posthumous swansong celebrate its 40th. Its message is more important than ever,” Roland says. Few would rebuff the ideals radiating from the artwork, this fête of hope – for peace, diversity and a community sharing in pride and determination. But for one attendee – a Chats Palace graduate – such ambitions are a mirage as cultural organisations are starved of funds.

And while those marchers standing to be counted may be immortalised on the streets of Dalston, the mural’s Riverian unity sits longingly in a city, and nation even, which has grown increasingly atomised, besieged by cynicism, suspicion and hate – as we were reminded last summer. In this sense, perhaps, very little has changed, giving its politics that much more bite and relevance.

Yet Peace Carnival’s cultural legacy is undeniable, both for the borough beyond. It featured on the cover of Hackney-founded drum-and-bass outfit Rudimental’s debut album, Home. The group later supported a campaign to protect and refurbish the mural, which saw it restored to its full glory in 2014. The extensive project was led by the local authority, along with cash donated by the band. The work itself was overseen by Paul Butler of LMP.

For 27-28 September this year, locals are organising a number of events and workshops to mark Peace Carnival’s official birthday. Alan May will be assembling a band of musicians linked to the Arkestra and others commemorated by the mural. As for the setlist? The still-wiry saxophonist “couldn’t possibly divulge”.