Souped Up

The Guardian got there first in October with a lovely recipe for a nourishing chicken soup, and several thumbnail variations, that could keep us going all winter.

Looking beyond Jay Rayner’s immortal description, ‘Your mum’s hug in bowl’ (which in fact he applied to Biang Biang noodles), for the ineffable Jewish chicken soup, we find that this sustaining brew has been valued for centuries as a medicinal prescription, and a restorative potion for invalids, frail old people and women in childbirth, as well as a political slogan attributed to Henry IV of France: ‘Si Dieu me donne encore de la vie je ferai qu’il n’y aura point de laboureur en mon Royaume qui n’ait moyen d’avoir une poule dans son pot’.

This translates as: ‘If God lets me live that long I’ll make sure that every worker in the land has the means to put a chicken in his pot’.

Henri IV was a wily and ruthless ruler, whose other often quoted remark was not as cynical as it sounds: ‘Paris vaut bien une messe’. In English: ‘Paris is well worth a mass.’

Born a Catholic, and brought up in the reformed religion by his Protestant mother, in the kingdom of Navarre at the foothills of the Pyrenees, he must have sensed as a child the need for a self-protective pragmatism in religious matters. So when in 1593 he turned Catholic in order to inherit the kingdom of France, thereby bringing to an end thirty years of horrible and destructive religious civil war and misery, he was acting in a sensible rather than cynical way.

We have no documentary evidence for when and how he came up with his ‘chicken in the pot’, a brilliant catchphrase that still tugs at the heartstrings.

It’s not clear what he meant by ‘laboureur’, peasant or honest hardworking citizen, or less likely, the poor and dispossessed, and it is uncertain what this ideal chicken in the pot signified. Was it ‘for the many not the few’ a basic comfort food, everyone’s inalienable right, or an aspiration, a luxury food for the élite?

The classic recipe for Poule au Pot involves simmering a good quality plump chicken in a well-flavoured broth along with vegetables (which could include onions, turnips, carrots, celery) and herbs. A frugal version is a way of extending the existence of a scraggy old hen, too old to lay eggs, too tough to roast, with whatever vegetables were around, and padding the dish out with barley or anything to hand.

Although we think of the essential Jewish ‘Chicken soup with barley’ as a frugal dish, in which maternal affection is the main ingredient, Claudia Roden pointed out in her monumental The Book of Jewish Food that around Yom Kippur the ritual sacrifice of many chickens, kapparoth, produced a glut of fowl, and created the paradox of a profusion of rich chicken dishes during a period of atonement. A recipe from Morocco on page 307 has a roast chicken stuffed with spiced couscous, which includes pistachios, dried apricots, saffron and pine nuts cooked in rich chicken broth.

Hoxton will never be the same now that Monty’s Deli has moved. Might the insidious flow of gentrification have spurred landlords towards unreasonable dreams of gain? But the memory of Monty’s roast chicken lives on, together with the ineffable schmaltz of the fat adding unctuousness and aroma to the fabulous ‘chopped liver’, and the voluptuous chicken soup with kneidlach that provoked my friend Professor Jerry Mars to raptures.

Cucina povera or a luxury food for special occasions, a politician’s view of the working man’s basic diet, or a ritual religious offering, chicken can also be a medicinal prescription and a tonic, prescribed by physicians for invalids, or for women in childbirth.

In Renaissance Italy childbirth was a welcome event. In 1438, and for many years after, the Black Death had reduced the population of Europe by one half, so instead worrying over yet another mouth to feed, pregnancy and the arrival of a child was cause for celebration and delight. Guests flocked to the house in their best clothes, bearing gifts, and were regaled with sweetmeats and comfits (the same sugared almonds and sugar-coated seeds and spices offered today at weddings and christenings).

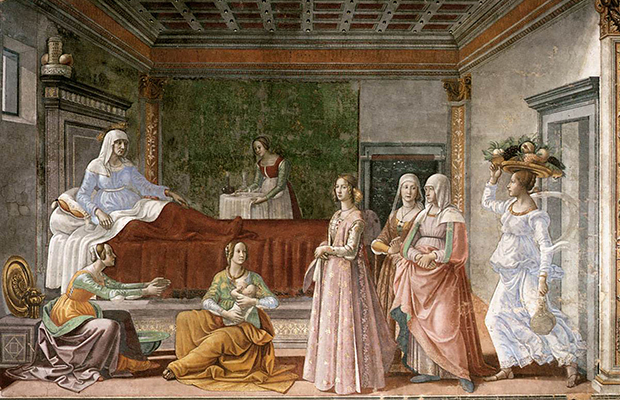

While the baby was washed and wrapped in swaddling clothes, the mother was cherished and propped up in bed with clean linen and silk and velvet curtains, and fed with nourishing chicken broth, and gifts of food, as can be seen in contemporary art of the time.

The Birth of St John the Baptist, painted by Domenico Ghirlandaio in the 1480s, in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, shows the Tornabuoni family flaunting wealth as well as piety, as they visit the new mother.

Not a mention of nursing mothers in Bartolomeo Scappi’s great work on cookery of 1570. He was feeding greedy cardinals and hypochondriac popes, and in the chapter on invalid food there are a lot of recipes for brodo consumato, a concentrated chicken broth made from a capon, not too old and not too young, killed the same day, and carefully plucked, rinsed and cut in pieces, then stewed in a sealed pot until reduced by two thirds.

Chicken is at the heart of biancomangiare, an enigmatic Renaissance dish, which bequeathed its name to our own rather horrible blancmange, a sweet but flavourless mess of milk thickened with cornflour.

The historic version is made from chicken breasts cooked in broth, then shredded or pulled with a fork and mixed with ground almonds, loosened with a bit of the broth, white breadcrumbs soaked in milk, mixed well together and cooked slowly to make a sort of cream, seasoned with salt, ginger, rosewater, verjuice and often quite a lot of sugar.

This aristocratic dish was an astonishing dazzling white, carefully eliminating anything that might give it the sludge colour of the everyday porridges or pulses of the poor, and often garnished with bright red pomegranate seeds or blue borage flowers.