Haggerston Baths: taking a dip down memory lane

Inside Haggerston Baths in 2015. Photograph: Simon Mooney

Any hopes that Haggerston Baths might open its doors again to the swimmers of Hackney have been dealt a mortal stroke.

Hackney Council last month announced a shortlist of three schemes for the empty swimming baths, and is set to run a public consultation early this year.

The trio of proposals all include retail units, art galleries, cafes, offices and one even floats the idea of a private members’ club.

But a swimming pool is conspicuously absent among the schemes, leaving members of the Haggerston Pool Community Trust, which has campaigned for over a decade for its restoration “bitterly disappointed”.

The baths, built in an imposing Wren-Revival style, were controversially closed and boarded up in 2000 after almost a century of use.

They opened in 1904, at a time when few working class homes had a bathroom.

Since their closure, the Grade II-listed building has suffered more than a decade of creeping dilapidation.

It has been squatted and used for illegal raves and its insides are now covered in graffiti.

A symbol of civic pride

The contrast between the wreckage of the baths today and the high municipal ideals that characterised its opening could hardly be more stark.

They were opened with pomp and ceremony on 25 June 1904 by the Mayor of Shoreditch.

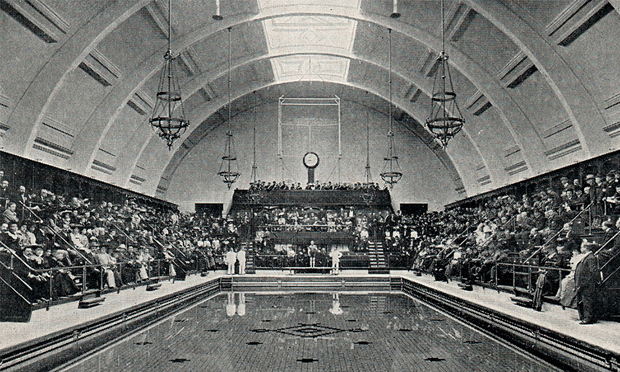

Haggerston Baths’ opening day in 1904. Photograph: Hackney Archives

At the opening swimming gala, the Vice Chair of the Baths and Washhouses Committee E.J. Wakeling “took the first plunge into the swimming bath amid loud applause”, and proceeded to swim the length of the pool underwater.

“I picture him in a suitably modest Edwardian bathing costume yet still cutting an ever-so-slightly irreverent figure in the middle of this (from our modern perspective at least) somewhat pompous manifestation of civic pride,” writes Michael Rosen in his book Dignity: Its History and Meaning.

Wakeling, a keen swimmer, was passionate about improving public health among the poorest in society.

He had been the secretary of one of London’s largest swimming organisations, and took the plunge into local government with the aim of establishing public baths.

In 1906, Wakeling wrote: “When, in 1887, my colleagues and I were discussing the question of providing Shoreditch with public baths and wash-houses, we ascertained that not more than one in 20 houses in the parish contained a bathroom.”

“We determined to do our best to remedy this existing evil, and on the principle that “man cannot live on bread alone’, we considered it our duty to offer facilities for enabled the humblest ratepayer to live under sound hygienic conditions.”

Built to last

Haggerston had become rapidly industrialised during the 19th century, with a gas works and chemical factory joining the traditional industries of furniture and shoe-making, weaving, and brick and tile manufacture.

Overcrowding and poverty was rife, with houses shared by three or more families. Haggerston Baths were designed by the renowned architect A.W.S. Cross, England’s leading architect for public baths, who designed Pitfield Street baths amongst many others.

The building was made of soft red brick, with Portland stone dressings and a colonnaded balcony topped by a cupola with a gilded weathervane in the form of a ship (see below right.)

The weathervane and cupola. Photograph: Simon Mooney

Inside, the glazed barrel-vaulted roof overlooked a 35-foot long swimming pool.

The washhouse at the back of the building was of more utilitarian design but still contained up-to-date washing troughs, wringing and mangling machines.

Residents could wash their clothes and bathe themselves in hot or cold water in 11 first class and 30 second class bathing booths, known as slipper baths.

And down in the engine room, three original coal-fired 28-foot Lancashire boilers, rumoured to have been salvaged from a ship, heated the water for the pool and baths.

Unlike more modern leisure complexes such as the Britannia, built in the 1970s and 80s yet already earmarked for demolition, Haggerston Baths was built to last.

“My experience is that the best materials, and the best materials only, should be used throughout all departments,” Wakeling wrote.

“This system of construction adds considerably to the first or capital cost, yet it is, in the end, an economical one, as it reduces the annual maintenance charge to a very large extent.”

A loan of £30,000 was originally requested for the construction of Haggerston Baths, but this figure soon swelled, the final total reaching £59,177 due partly to the Bath and Washhouses Committee’s insistence on using the best materials.

The Boiler Room. Photograph: Simon Mooney

Modernisation

During the Second World War, Haggerston Baths suffered bomb damage and the pool closed.

From 1946-1954, Jane Entwhistle lived in the flat at the top of the building. Her father was Superintendent of Haggerston and Pitfield Street Baths.

“All the time we were at Haggerston new improvements were being made,” she recalled.

Modernisations were carried out in 1960, leaving only the female bathing booths.

Then in the 1980s a new boiler was fitted, and the pool was reduced from 30.5 metres to 25 metres in length to accommodate a teaching pool. New changing rooms were put in, the old changing cubicles and poolside seating were taken out and a balcony was added, making more room for swimmers and spectators.

In 1988, despite these alterations, English Heritage bestowed Grade II-listed status on Haggerston Baths, reporting that: “The Baths are a unique and important part of Hackney’s heritage.”

Deterioration

Yet only 12 years later, on 11 February 2000, a notice of temporary closure on health and safety grounds was fixed to the padlocked doors of Haggerston Baths following more than a decade of neglect and poor maintenance by Hackney Council.

Writing in the London Review of Books in 2015, the writer Iain Sinclair, a regular at Haggerston Baths since moving to Hackney in 1968, recalls “my annoyance, towel roll under arm, clutch of ice at the heart, after too many previous experiences of how elastic that ‘temporary’ qualification could be. Schoolchildren arriving for their weekly session were turned away. They would never return.”

Haggerston was at that time Hackney’s main swimming pool.

Eight sports clubs and 10 local primary schools used it for weekly swimming at the time of its closure.

Pupils at Laburnum Primary, on the site of what is now Bridge Academy, were left without any swimming provision at all, reportedly leading every child at the school to write a letter of complaint to the council.

“The present situation is dire,” Adam Hart, a local resident and director of Hackney Co-operative Developments, is quoted as saying at the time.

“Haggerston Baths are in the poorest part of the borough and now there is no swimming provision at all – it’s a serious issue of social justice.”

Haggerston Baths in 2015. Photograph: Simon Mooney

Spectre of Clissold

At the time of the Haggerston Baths closure, the cost of renovation was said to be around £300,000. But the council was in debt and haemorrhaging money on the construction of Clissold Leisure Centre, its new grand project that was meant enhance its reputation and serve as a focus for regeneration. An internal report to the council in February 2000 recommended the “transfer of revenue funding from Haggerston to Clissold pool”.

Clissold Leisure Centre was meant to open in 1999 in time for the millennium.

The original budget for the leisure centre in 1996 was set at £7 million, but after Sport England designated Hackney a priority area the plans were revised and the budget was set at £11.5 million.

Yet when Clissold opened in February 2002, three years late, it had cost £34 million.

Then, 22 months later, it closed – ironically on health and safety grounds.

Campaign group Not the Clissold Leisure Centre detailed a catalogue of defects on its website. They included the children’s changing areas being located next to two-metre deep water and dirty water from showers flowing into the pools.

“If you seek political hubris, overarching architectural ambition, millennial folly and evidence of the decline of local authority expertise in one building, this is where you should come,” said the architecture critic Jonathan Glancey in the Guardian.

When Clissold Leisure Centre finally reopened on 15 December 2007 it was at a total cost £45 million (seven and a half times the original budget). The project was more than eight years late and had been such an unmitigated disaster that the council had ended up taking legal action against the architect, quantity surveyor, consulting engineer and contractor.

Great lengths to save Haggerston

“While the millions stacked up, Haggerston paid the price,” writes Sinclair adroitly. The Baths all the while lay empty and neglected by the authorities – to the extent that by 2015 the original estimate of £300,000 to restore the baths had swollen to £25 million, after vandals and squatters took their toll. This was despite a groundswell of support among borough residents, which led to the establishment of the Haggerston Pool Community Trust.

Haggerston Baths in 2015. Photograph: Simon Mooney

The Trust held meetings and protests and petitioned the council to reopen the pool. In 2004, to mark the 100th anniversary of the opening of Haggerston Baths, the Trust organised the first Laburnum Street Party, a community festival held to raise the profile of the campaign.

It looked as though the campaign was working. In 2006, a feasibility study determined that £21 million would be needed to reopen the pool as a Health and Wellbeing Centre complete with gym, GP, dentist and hydrotherapy. The plans were endorsed by the council’s cabinet in March 2009, but were kicked into the long grass once the recession hit.

False dawns

This was but one of a series of false dawns for the pool campaigners.

In 2014 campaigners launched a petition calling for the derelict baths to be listed as an Asset of Community Value – a type of protected status a number of pubs in Hackney now enjoy.

But their bid was rejected and former Hackney mayor Jules Pipe said the council’s “ever-shrinking” resources meant Haggerston Baths could not be a priority.

Then in 2015 Mayor Pipe invited developers to submit “expressions of interest” for the building’s future.

The council received 29 proposals including four that included a swimming pool. Some plans reimagined the Baths as a hotel, a museum and even a brewery.

The three finalists, announced last month, will be up for consultation in the New Year. As the Hackney Citizen has reported, from the outset each scheme seems remarkably similar.

Pipe’s successor as mayor Philip Glanville has said the council spent the best part of a year negotiating with a developer whose proposal included a pool. But not being able to secure “the reassurances needed that the scheme would actually be delivered”, it appears the council has thrown in the towel.

Main entrance to Haggerston Baths. Photograph: Hackney Council