Coronavirus: ‘Now is the time to change our education system for the better’

Photograph: David Hawgood

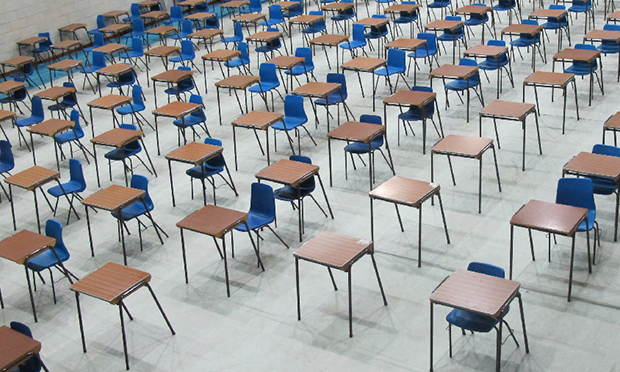

For school students in the UK, exam results day has become one of teenage life’s most defining moments, a rite of passage for each passing year group.

Most adults can recall tearing open their exam results, and whether they were struck with feelings of pride or sinking disappointment at what they saw.

On results day, it feels like the entire nation observes the spectacle. Local reporters decamp outside school gates taking obligatory photographs of students who have been successful exploding in paroxysms of ecstatic relief, their results papers waved high in the air.

The pandemic means school leavers this year will not partake in this ritual, resulting in many wondering what the future holds for their education and for their first steps into the job market.

For those progressing to university, teaching will not occur in the traditional format.

Last week, the world was stunned by the announcement that Cambridge University was moving all its lectures online until summer 2021, and it seems likely many other higher education institutions will follow suit.

Although universities are resolute that they are doing everything possible to ensure next year’s courses will be as academically rigorous, the social dynamic of university life will be radically altered for the time being.

Many people consider university to be a seminal coming-of-age experience where taking part in Freshers’ Week, living independently for the first time in halls and forming relationships are as important as the books you are set to read in the library.

Although this might be an overly romanticised view of student life, many A-level students have this experience in mind when they apply.

The Office for National Statistics found that between April 2016 to March 2018 household debt totalled £1.28 trillion, leading many to wonder, in a world in which personal debt is already so significant, if the costs of this new pared-down university experience are worth it.

Schools and colleges in Hackney have been trying to support students at this unsettling time.

The borough’s director of education Annie Gammon told the Citizen: “This has understandably been a very challenging and anxious time for all pupils – but especially those who were due to sit exams and move on to further education, training or employment.

“Staff have put in a lot of time to ensure that the grades they give are accurate and a fair assessment, based on solid evidence.

“Teachers are in touch with their students and try to have at least one phone call a week to see how they are and to offer pastoral support and advice on their next steps.

“Where students are applying to university, this can include help making final decisions regarding UCAS, support finding online materials about things like finance or even their chosen subjects.”

Deputy Mayor Cllr Anntoinette Bramble also acknowledged the considerable difficulties faced by students, adding: “I’d like to say a huge well done to all of our teachers, school staff and pupils for finding their way through this difficult time, and make sure that all of our year 13 students know that we are thinking of them.

“This isn’t how they will have imagined their last few months at school or college, and I know headteachers and principals are thinking of ways to mark their achievements when it is safe to do so.”

There are concerns about how the drastic changes in daily routine and the delivery of education will impact on young people’s mental health.

A spokesman for Queen Mary University, which is close to Hackney and attended by many local residents, told the Citizen that the welfare of students is its “top priority” and that it has set up a number of initiatives “to ensure we minimise the impact of coronavirus”.

The spokesman confirmed that the university’s mental health support has now transitioned online and students are able to access one-to-one emotional support from those trained in online counselling.

We should not forget that prior to Covid-19 there was already a youth mental health crisis, aggravated by the continuous weight placed on young people’s shoulders to perform academically, but the burden to achieve is not just restricted to children.

The rise of intensive parenting – imported from America – has left parents and carers under constant financial and emotional strain to ensure their child has the best of everything.

Many feel under perpetual pressure to ferry their children to a never-ending schedule of music lessons, language lessons and tutoring, all whilst juggling full time, stressful careers themselves.

The phenomenon of intensive parenting has also been blamed for exacerbating inequalities in America, as highlighted by The Atlantic magazine, by disadvantaging the children of poorer parents, who are unable to allocate the same amount of time and money to furthering their prospects.

Young Minds is a national organisation that advocates for better mental health outcomes for young people in the UK.

Its annual report for 2018/19 found that more than a million children in the UK have diagnosable mental health problems, but only one in four will ever gain access to relevant support.

The report also highlighted that for those who do receive help, the average waiting time for a first appointment with Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services is six months.

The pandemic has exposed many deficits in our public services caused by chronic underfunding, provoking national discussions around how we reconstruct these services.

There has never been a more relevant time to reflect on our education system and on what we emphasise is important to children, so the next generation is happy and well balanced.

For years, teachers have called for meaningful changes to the curriculum so instead of the singular focus on training students to pass exams, equal attention is given to nurturing a sense of social responsibility and mutuality.

Although previously this argument might have been dismissed, mutual aid groups now provide definitive proof of the importance of community and reciprocity to the cohesion of society.

Teachers enter the profession with these values in mind, but many leave disillusioned with being forced to spend the lion’s share of their time endlessly marking papers and prepping children for exams.

Given the current context, it feels reasonable to incorporate these principles into the curriculum once schools re-open.

We should also recognise young people have been saying they want a national curriculum that engages and responds to the social challenges of the era we live in.

Last year, across the planet, over a million youngsters protested world governments’ intransigence over addressing climate change.

The UK Student Climate Network is a group of young people, most under the age of 18, who orchestrate street protests to challenge the collective inaction.

The group claims to have organised more than 850 demonstrations during 2019.

Many young green activists have been skipping lessons, not because they don’t want to learn, but because they feel they can better advocate for critical societal changes in street protests outside the classroom.

One of my own defining memories of formal education occurred in the last few weeks of my school career.

Having never been particularly academic during my GCSE years, I decided I would amp up my efforts and focus during my A-levels to achieve the best results I could.

My hard work appeared to be paying off until disaster – as I considered it at the time – struck during my History exam.

I had doggedly revised for months, assiduously memorising key facts about the English Civil War, but when I opened the exam paper with trembling hands, I was utterly thrown by what lay in front of me.

In hindsight, with a calm temperament and a clear head, it was a solvable question, but in the frenzied panic that enveloped me I convinced myself I could never decipher the answer.

I closed the paper without writing anything and walked out of the hall, trying to ignore the curious stares trained on me from my fellow students.

A decade later, trying to piece together the mindset of my 18-year-old self, it was obvious I had suffered a panic attack.

I have not experienced anything similar since, and although at the time it did not occur to me, I am now certain the attack was brought on by the colossal pressure I had heaped upon myself to ace the exam.

I am sure my experience is analogous to so many other students and has been replicated innumerable times in exam halls up and down the country.

I was lucky to have had very supportive teachers who were able to calm me so I could return to the exam hall to complete my paper.

The episode is not significant to anyone else, but it is indicative of the damaging emotional impact on individuals of an education system that places an inordinate amount of pressure on learners.

When schools re-open, and this should only occur when it is safe to do so, we must recognise that students will be disorientated and scared. Many may be traumatised, having witnessed family members losing their jobs and even their lives.

We cannot subject them to the same unforgiving, brutal exam treadmill that has failed so many students who have gone before.

Now is the time to consider how we can change the education system and rebuild it in a better way.