Shoreditch – land of hope and opportunity

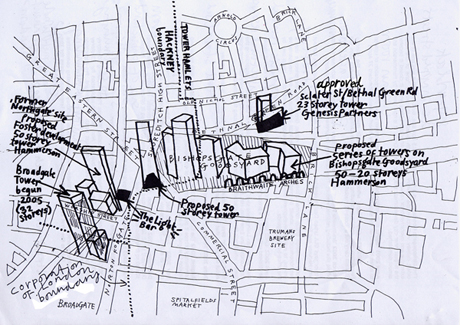

Artist's impression of last year's plan for Bishopsgate Goodsyard and surrounds (Disclaimer: artist's impression only)

THE disused Bishopsgate Goodsyard and adjacent sites have been eyed by developers and local residents alike for their potential to reinvigorate the heart of Shoreditch. A temporary reprieve from the threat of high-rise development was the result of an unlikely combination of local opposition and economic hard times.

Now the Bishopsgate Goodsyard site, a five-hectare patch of mud, rubble and remnants of historic buildings, could be the focus of an innovative new type of planning that involves all stakeholders in a site, known as community planning.

In June 2006, Hammerson plc, Britain’s fourth biggest property developer, unveiled plans for a £700 million Bishops Place development, on a smaller site to the west of the Goodsyard.

In July of last year, Hammerson applied for planning permission to demolish the Light Bar building on Shoreditch High Street, which forms the north-west corner of the site on which the complex was to be built.

An extended campaign of community opposition to plans for Bishop’s Place followed. The plans included the demolition of the historic Light Bar building. The protest against these plans included a letter of objection from Hackney’s recent interim Head of Planning Chris Berry, after he had resigned from the Council.

In line with the recommendations of English Heritage, Hackney Council finally agreed to protect the building with conservation area status, and retain this Victorian industrial building.

At the same time, the recession was making plans for construction on this site increasingly precarious, and it was becoming unclear when Hammerson would be able to begin building work.

Community campaigners are often typecast by developers as being nostalgic, sentimental, NIMBYist and generally opposed to change. But in this case, Hammerson has been obliged by circumstance to reconsider its plans and has acknowledged the relevance of public opinion and local residents’ role in deciding the future of their neighbourhood.

Rob Allan, Assistant Director of Hammerson said: “Hammerson’s approach is to consult with the local community and other stakeholders at each stage of a development.

“In the case of our regeneration plans in the Shoreditch area, we were restricted until the end of the emerging draft Interim Planning Guidance for Bishopsgate Goodsyard.

“Now this public consultation on the draft Interim Planning Guidance has come to an end, we have adopted our usual approach to consultation and have held a number of constructive meetings with OPEN Shoreditch as well as other local stakeholders.”

OPEN Shoreditch, a coalition of local community groups, has been at the forefront of championing community concerns.

Its Co-Chair Rebecca Collings explains why local residents care about this site: “Concern has been generated by affection and respect for the neighbourhood. We do not want to see it obliterated. We live and work here. This easing of development pressure has given local authorities renewed energy to get things right.”

“The big challenge now is to get people involved,” said Collings, before going on to emphasise what an opportunity it would be for local residents to participate in this way.

“At first glance, these community planning events might seem to be commonsense, but they are in fact quite innovative. The idea is that anyone and everyone who has an interest in a particular area is invited to sit round a table to thrash things out to come up with an acceptable solution there and then.”

In this way years of applications, objections, appeals and so on can potentially be short-circuited through direct dialogue between interested parties.

“The idea is that the community planning process results in something for everyone – enhancement of existing positive neighbourhood qualities, improvements to local amenities, profit for the developers, and the potential realisation of community aspirations for local people,” explained Collings.

In the meantime, architectural practice Terry Farrell and Partners has been commissioned by Hackney and Tower Hamlets to produce development guidelines for the Goodsyard site.

As part of the process the architects and representatives of the developers Hammerson and Ballymore agreed to a walkabout through the character area north of Bethnal Green Road to help their understanding of how development would impact local residents. According to Collings, both the architects and developers found this experience informative and felt it would help them to create a more sympathetic and responsive development.

Locals concerns include: potential loss of light (many leading artists have their studios north of Bethnal Green Road); loss of local character of a unique part of London; swamping of local independent traders; and the encroachment of the City into a unique residential and mixed-use area.

Local residents favour exploring interim uses for the site, to reduce the negative impact of its dereliction, for example, re-commissioning the swimming pool under the arches of the historic Braithwaite Viaduct that adorns the centre of the site; as well as theatre and other cultural facilities that could serve as interim uses or permanent features.

But whatever physical structures are eventually erected on this site, a more intensive and participatory consultation process could expand a successful model of citizen involvement and partnership in deciding how local neighbourhoods should be developed.