Bring on the artichokes! Gillian Riley on Caravaggio, veg and violence

Detail from Giovanna Garzoni’s Artichokes in a Chinese dish with rose and strawberries (c. 1650)

I’m glad I wasn’t there on 24 April 1604, a hot night in the sleazy backstreets of Rome, between the Pantheon and the Campo de’ Fiori, when Caravaggio the painter flung a dish of artichokes at the head of an insolent waiter.

He had ordered eight of them, four cooked in butter, four in olive oil. They arrived on the same dish. ‘So which is which?’ he demanded. “Sniff them and see…” sneered the soon-to-be victimised server.

Caravaggio said “Se ben mi pare, becco fottuto, si crede di servire qualche barone!” (“Looks to me, you fucking cuckold, as if you thought you were serving some gang boss!”) and the waiter got what was coming to him: not badly hurt, but the incident was reported to the police, and ended up in Caravaggio’s dossier along with much GBH and the carrying of a prohibited weapons, finishing with the murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni.

The point here is really gastronomic; artichokes were once a rare and expensive treat, but by the early seventeenth century were trendy popular vegetables, cultivated locally, but still deserving respect and cooked in various ways, as they are in Rome today. So they figure in still life paintings by Caravaggio and his contemporaries as available luxuries, their visual appearance, all curling baroque fronds and pinkish green buds, a foil to the rounded fruit and pointy asparagus of the composition.

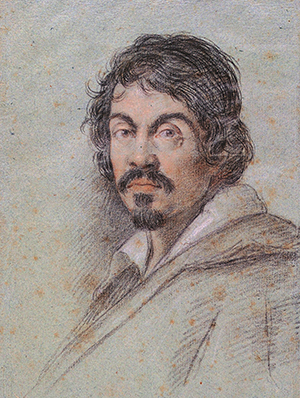

Mugshot: a portrait of Caravaggio by Ottavio Leoni (c. 1621)

In Rome today they are trimmed, smashed flat and deep fried in olive oil, carciofi alla giudea, once a Jewish speciality, now a universal treat. The other way, carciofi alla romana, involves cutting away all the inedible bits and stuffing the exposed heart with a mixture of garlic, salt, pepper and mentuccia, a herb of the mint family, calamenta nepeta, and cooking them slowly in olive oil and water, stems uppermost, until soft enough to cut with a spoon.

You’d need the fresh young artichokes, cimaroli or romaneschi, to recreate these delicacies, hard to find here, so it is better to follow the recipe Leila McAlister offers in Leila’s Shop, a food store and a good place to eat in one of the prettier, maybe the only pretty, parts of Shoreditch, using artichokes from her own store.

Rachel Roddy of the blog ‘Rachel Eats’ gave a version of this recently in The Guardian. Carefully trimmed of the inedible parts, what’s left of the artichokes (not much) is braised with butter beans, onions, carrots, leeks and celery, with olive oil and splash of wine, some good homemade vegetable stock, and a pinch of chilli, to make a delicate, but rich and satisfying fragrant stew.

Knife crime and gang warfare alongside the sophisticated clubs and avant garde studios of Hackney would have been familiar to Caravaggio the painter, whose violent episodes seemed to come from a need for the adrenaline of conflict. After weeks of solitary, patient, perfectionist work on a painting, he would collect his fee, reach for his sword, and strut the streets of Rome searching for and creating mayhem.

His right to carry a sword, as member of the household of a Roman cardinal, was more badge of honour than for self defence. A page carried the sword, and when charged with possession of two even more offensive weapons, he pointed out that the pair of compasses concealed under his cloak were measuring instruments, used to gage the position of items in a still life painting, where accuracy mattered so much.

Today Caravaggio would find benign substitutes for street violence in the espresso machine and the combustion engine; a double espresso at Venetia’s and a short ride on a 393 bus in hurry to Clissold Park might have made a dent in crime statistics, with hopefully less roadkill.

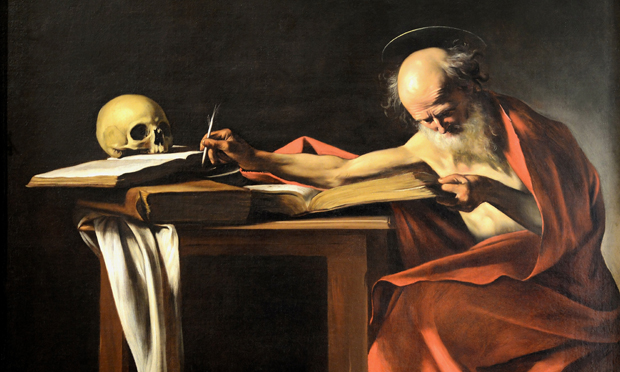

One of Caravaggio’s most famous works, St. Jerome (1605-6)

There is no stretch of the imagination that allows us to envisage Caravaggio as a dutiful Roman legionary, toiling up Stamford Hill, out of step all the way to Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall. Though he might have made a detour to the left up Stoke Newington Church Street to trash L’Antica Pizzeria da Michele. The painter had spent some time in Naples and knew the real thing. Enough said.

To be fair, the tomato had not then gotten its stranglehold on Italian gastronomy, and what Elizabeth David saw as a malign tide of red gloop submerging the subtleties of earlier cuisines, was then hardly a trickle. There are no tomatoes in any of the still life paintings by Caravaggio and his followers, and only one glimpse of a chilli pepper, while botanists saw them as decorative pot plants, likely to do more harm than good.

Da Michele’s austere offering of the two traditional Neapolitan pizzas, margherita and marinara, would be more successful with just a smear of their San Marzano tomatoes, rather than the flood of the stuff that makes the dough go all soggy in the middle. The origins of pizza are in cucina povera when a thin layer of rapidly cooked bread dough, with whatever cheap and tasty things that came to hand, fresh herbs, cheese, olive oil, was a cheap snack for the poor. Mozzarella was local and inexpensive – so don’t let silly foodies get away with buffalo mozzarella, and charge extra for it, it’s far too watery for pizza. Though it’s lovely in a salad.

Fleeing the death penalty for murder might have brought Caravaggio to London as well as Naples. He would have got on well with Italians like John Florio, who taught Italian to English aristocrats who needed to keep up with fashionable literature, and Giacomo Castelvetro, who advised the nobility on their gardens (Italian of course).

We can imagine them sharing a jar or two in the Mermaid tavern, moaning about the terrible English food (too much meat and sweet things, not enough salads). Although a staunch Protestant, Castelvetro, who could not harm a fly, would have had the tact to calm the bellicose Caravaggio, and they might have shared memories of their youth in Northern Italy, of the botanists and plant collectors in Florence and Bologna, and the wonderful crops of artichokes and asparagus arriving daily in the markets of Venice and Milan, while behind their backs the market gardeners of Hackney were getting quietly on with their own horticultural innovations.