From McQueen to green

Brett Mettler with her upcycled creations at Bethnal Green’s Young V&A. Photograph: Josef Steen

Despite its reputation for being generally aloof, much like finance, the world of fashion is not immune to those three little letters – ESG.

In fact, the industry has been more than eager to talk up its environmental credentials in recent years, with sustainability predictably becoming a core theme of trade events over the past decade.

In 2023, Copenhagen Fashion Week’s organisers set several ‘minimum standards’ for participants – recyclable set pieces, a ban on fur, and designs only on at least 50 per cent of recycled materials.

It’s a welcome change, even if the cynical among us might boil it down to good PR. But despite strides being made, whether in earnest or not, it remains to be seen how far globalised industries like these are willing to go to rein in supply chains and decarbonise.

After all, outsourcing is king in the world of fashion, whether fast or slow. In production, “very few brands know where their stuff comes from in the supply chain”, according to environmental scientist Linda Greer.

This complexity and lack of transparency means estimates of the industry’s carbon impact range from four per cent (McKinsey and the Global Fashion Agenda) to 10 per cent (United Nations) of overall global emissions. Expectations – and prices – are high, but too often, talk is cheap.

In this context, Hackney-based designer Brett Mettler seems to be the real article.

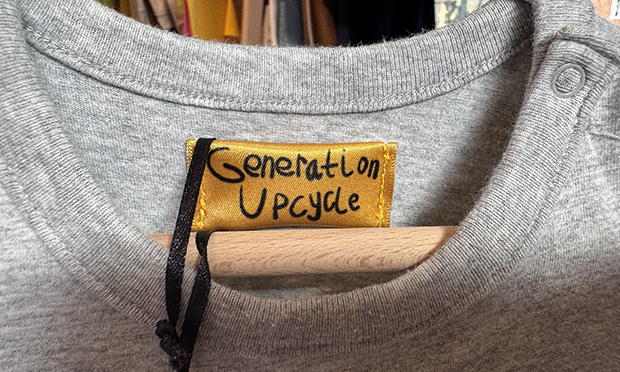

For the last few months, the Philadelphia-born couturier has been displaying her collection of upcycled garments at the Octopus Club on the upper deck of the Young V&A. Her ‘brand’, Generation Upcycle, brings new life not simply to old garments, but to the meaning of the word homespun.

I meet Brett at the shop on a wintry Saturday morning at the “bonkers” museum, surrounded by infants. She is, unsurprisingly, immaculately dressed, with a sleek, bleach-blonde bob that reflects her zestful charm.

For the past five years, she has been rummaging through garments destined for landfill and running around thrift shops to pick up torn or “unsellable” items. Brett is a Woolcrest addict – sifting through the deadstock of fashion companies that would otherwise be buried in the ground or burned up.

“My absolute favourites are damaged garments – with kids’ clothes, that’s pretty easy actually.”

Brett explains how to create ‘suited and booted’ shorts. Video: Brett Mettler

We probably couldn’t be further than the house of the late Alexander McQueen, where Brett cut her teeth. But it doesn’t take long for her to make her journey from high fashion to upcycled children’s clothes appear completely natural. After all, Mettler is an insider shaped by the claustrophobic, muzzle-flash world of haute couture.

“It was like a Marine’s hazing. You’d be up for most of the time, becoming extremely sleep-deprived over years,” she says, recalling the nights spent kipping on a studio couch.

The fashion world’s atmosphere of high pressure, rejection and constant culling of both people and ideas will be familiar to many, but it begins at college.

“Central Saint Martins will teach you to think, but the industry will teach you everything else. If you really want to be excellent at execution, you need to learn it from somewhere else.”

As for the industry itself, infamous for being both mad and merciless, under “Lee” McQueen’s wing, Brett was exposed to its wilder, philosophical power. In the right hands, it seems, scissors and fabric can be as powerful as the pen, the paintbrush or the movie camera.

“McQueen’s obsession with the natural world, art history, and the darker side of the human psyche was part of the reason I got into fashion. There’s something exquisite about the beautiful and the grotesque together—getting that balance just right is fundamental.”

Such imagination has its price.

“We would work on these insane projects,” Brett says, namely a wedding dress made from holographic silk organza. Semi-transparent on one side, on the other it resembled “the deepest depths of the sea, with ghost-like creatures floating in it”.

This futuristic show-stopper alone used fabric worth £1,000 per metre, backed by months of work. Yet even after this “feverish” toil, McQueen came in three days before and cut it into three different pieces due to it dominating the collection.

“In that moment I realised I was around true greatness. I absolutely love and aspire to have that level of bravery – no matter how great I think something is, that I could burn it.”

Brett’s father taught her about ‘reusing materials and respecting resources’. Photograph: courtesy Brett Mettler

This seems a world away from Brett’s current gig, where this kind of waste is spurned, and detritus now the raw material rather than the price of greatness. Both the pandemic and giving birth to her daughter catalysed this shift in perspective and pace.

“I was always going a million miles per hour, obsessed with art for art’s sake, not thinking deeper about consequences. Having a child and the pandemic forced that to stop.”

That said, her eco-consciousness has clearly been gestating for a long time, handed down by her parents. Her father, an environmentalist and performer, instilled an ethos of reuse.

Motherhood crystallised these lessons further: “I started thinking about what my dad had taught me, about reusing materials and respecting resources.”

Brett is also now blessed with a different breed of creative director, although equally ruthless. Her daughter, Quinn (Gaelic for ‘wise counselor’), has “happily” filled the critic’s chair.

“She will quickly tell me if a piece is working or not, or if she thinks we should change direction. And that’s really good for me. I’ll start getting attached to stuff, and she’s like, ‘Nope.’”

This mention of fashion’s consequences, but also the inexhaustibility of fabrics and materials, seems to underline that the philosophy and products of upcycling are on par with the aesthetic sensibilities of high fashion. Like alchemy, it is about “turning trash into gold”.

When it comes to sustainability and climate politics, we often hear that no-one is too small to make a difference. There is a certain truth here. On average, each Brit produced around 14 kilograms of clothing waste last year. The scale of the problem is not lost on this deadstock devotee, but that’s unsurprising—I am talking to an alumna of Alexander McQueen and Gareth Pugh, after all.

“Even if it’s just me and a handful of other upcyclers doing this, we’re still pulling things from landfills and giving them a second life,” Brett says.

Generation Upcycle symbolises an optimistic way of thinking. Photograph: courtesy Brett Mettler

She might be comfortable positioning herself as something of a maverick – someone who has been up close, absorbed the industry’s excess and come out the other side. There’s something here about time, and the notion that upcycling is not simply an eco-conscious choice but a way of reimagining objects and their value.

“A piece of clothing holds stories. When you wear something upcycled, you’re not just wearing fabric—you’re wearing its past, its history.”

The practice is therefore a precursor for artistic invention but also reinvention – of the things we grow attached to but forget their potential for change. It’s what allows this brand of upcycling to be both wholesome but also unsentimental.

So, will the fashion industry wake up and smell the coffee?

“I think there’s inevitable change. It has never been a sustainable system and we’re coming to the head of it now. You can already see a lot of interest – a lot of brands do pseudo-upcycling, showing that the public themselves want change. It’s more challenging, but authentically upcycling is more interesting, too.”

Material incentives still drive fashion, but Generation Upcycle represents a more optimistic, future-oriented way of thinking—one that values reinvention not just as a bulwark against waste, but for its own sake.

You can follow Brett Mettler and Generation Upcycle at instagram.com/genupcycle.