Richard Mosse, Incoming at Barbican Curve: a shattering view of humanity and the inhumane

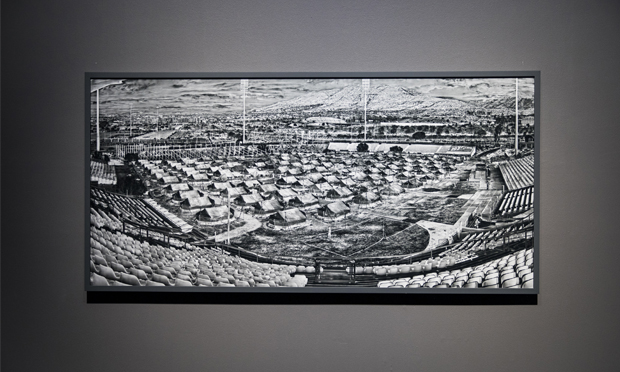

A scene from the Incoming installation. Photograph: Tristan Fewings / Getty images

Using a military grade camera, capable of detecting a human body from more than 30km away and identifying a person from 6.3km, Richard Mosse exhibits photographs and video installations shot in refugee camps in Greece.

Mosse said in his statement about the show: “I am European. I am complicit.” If his goal was to impress the same feelings upon his audience, it is something he certainly achieves. The sense of helplessness felt as an audience member is palpable. We are made aware that we have no control over the fate of the people shown in the films and photographs. The pin drop silence in the gallery, despite it being full, is testament to the show’s effectiveness.

The video images, made with cinematographer Trevor Tweeten, is unmistakably surveillance footage. The piece ‘Grid’, shown over 16 screens, shifts and changes not allowing the viewer to focus on any one thing for too long. It is unsettling and disorientating and furthers the sense that the plight of the people in front of you is out of your hands. It feels as though Mosse is making an implied accusation of passivity and commenting on the voyeuristic way in which Western society is viewing the very real situations faced by migrants and refugees. By forcing us to see immigrants as the government or the military sees them, Mosse inspires a reflection on our current levels of empathy and our inaction, albeit without much subtlety.

The gallery is dark and the screens’ content seems more overwhelming for it. Adding to the claustrophobia, the soundscape provided by composer Ben Frost follows you around the gallery in a haunting fashion. It has a depth that, when combined with the images and videos, feels as though it not only gets under your skin, but burrows into your organs. In the title piece ‘Incoming’ footage drifts between scenes of deprivation and struggle to children playing and people having fun.

The music that accompanies remains somewhat ominous, but demonstrates a lift in spirit and reminds the audience of the humanity of displaced people. Collectively the artists succeed in providing a new perspective into the simultaneous kindness and cruelty of humankind.

The exhibition is also visually breathtaking. The figures of people in black and white thermal imaging means they look ethereal and at times, due to the slowed pace of the film, take on a spectral form. Perhaps again a nod to the lives lost during the current and past migrant crises. Mosse captures upsetting subject matter with delicacy and poeticism and the combination of the two creates something immensely emotive with a complexity that mirrors the aspects of human nature he endeavours to portray.

The exhibition is painful, poignant and important in developing our understanding of difficulties faced by refugees and migrants today.