Further Education feels the squeeze as government pushes apprenticeships

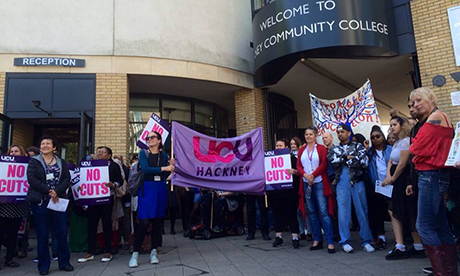

Students and staff protest against cuts outside Hackney Community College.

George Osborne announced plans for a levy on large businesses to help fund his target of creating three million apprenticeships by 2020. This, it appears, came in response to a scathing report by Professor Lady Alison Wolf criticising the government’s FE funding plan and was tentatively welcomed by many – not all – across the sector.

It was a lukewarm reception that felt much like a short, sharp sigh of relief, as the levy, coupled with a controversial switch from higher education maintenance grants to loans, implied a moment’s reprieve for the battered and bruised funding of adult learning.

I say reprieve because it was feared the cost of more apprenticeships would mean more immediate cuts to classroom-based FE, and it was hoped that scrapping university grants might ease financial pressure on the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) – giving FE colleges a little breathing space.

The repose was short lived. Within weeks a further 3.9 per cent cut to the adult skills budget, which finances non-university education and training for those aged 19 plus, was tacked on to the 24 per cent loss already confirmed for 2015/16. Combine this with a 40 per cent crash in funds since 2010 and the outlook is bleak. The University and College Union (UCU) believes the cuts could affect 400,000 students in the next year alone, and Hackney is feeling the strain.

Before the summer break, the Hackney Citizen reported that Hackney Community College (HCC) has been forced to shut down three art courses because of the cuts. Local artists and arts organisations turned out in force to march in protest over the closures and in support of the college, while the UCU has been lobbying parliament on the issue.

Despite the financial pressure it’s under, HCC responded positively, with staff working to ensure that all affected students secured places on relevant courses.

Principal Ian Ashman said: “As a result of the government funding cuts and increases in national insurance contributions, Hackney Community College needs to reduce its costs by at least £2.9m for the coming year. It will achieve this in a number of ways, including an increase in loan-funded courses, commercial training and through new partnerships with local businesses.”

While Mr Ashman welcomes the government’s proposed levy on businesses and is optimistic about greater regional engagement with employers’ demands, he is clear that what colleges need are a few years of stability in funding and direction.

For many, the government’s push on apprenticeships does little to alleviate the fear that in years to come an education in the arts simply won’t be accessible to anyone unable to pay for it, which threatens to make such learning an almost exclusively middle-class endeavour.

Left without choice

HCC media tutor and UCU representative Nicola Godlieb said: “The new trend for apprenticeships has meant traditional creative subjects such as visual art have struggled to compete in this short-termist, numbers-driven economy.

“The result is that some young people from underprivileged backgrounds aren’t being given that chance to choose to progress to higher education… We need to try harder to safeguard these areas for all young people. Apprenticeships are important but there has to be equal choice.”

Comedian and co-founder of The Arts Emergency Service Josie Long, who studies maths at HCC and has been campaigning against the course closures, said: “The fact that Hackney Community College is being made to close its art courses is completely reprehensible.

“Art foundation courses allow young people from backgrounds without privilege to access arts degrees – and why do we need diverse voices in the arts? Because otherwise all you get is fucking Mumford and Sons over and over again. And that is not what we want.”

‘Soft’ options suffer

Common rhetoric implies that creative courses are likely to suffer during periods of austerity because they are viewed by many as ‘soft’ options; however, findings from Arts Council England and the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) suggest they are anything but.

The research states that the output of the UK’s creative industries grew by 9.9 per cent in 2012-13, faster than any other sector besides financial services. For every pound spent on arts and culture, an additional £1.06 is generated in the economy.

In addition, a 2015 report produced by the Warwick Commission – launched by the University of Warwick – on the future of cultural value explains: “A quality cultural and creative education allows people to develop rich expressive lives, and it is essential to the flourishing of the UK’s cultural and creative identity and the Cultural and Creative Industries that this opportunity is not limited to the socially advantaged and the privately educated.”

Putting the economic and cultural merit of arts-based courses aside, a lack of support for adult learning is indicative of a government disinterested in giving those who fail to achieve qualifications the first time round – at school – a second chance. It’s no surprise that individuals who suffer in this regard are often society’s most vulnerable.

Part-time adult courses, for example, allow single parents and those unsuited to school and university to re-enter education. Such courses also enable those in work to retrain for promotion and keep in touch with the fast-changing demand for skills at a time when the workforce is, crucially, getting older.

With points like these in mind, last year’s suggestion that savings on welfare could be used to bolster the narrowly-focused apprenticeships push is a tough irony to swallow, particularly considering the government’s stress on social mobility.

Essentially, the future of adult non-university education is still unclear. Post-16 education and training reviews are currently underway, so more should emerge soon; the devil it seems will be in the detail. But with Shadow Education Secretary Lucy Powell and Shadow Skills Minister Gordon Marsden recently speaking up for the protection of FE colleges, there is cause for some optimism.