In cod we trust: there’s no plaice like Hackney for fish and chips

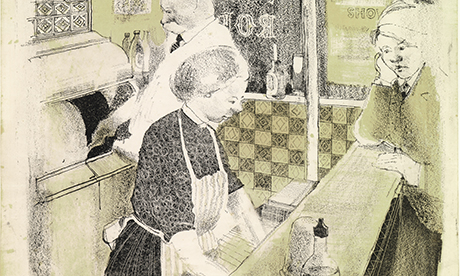

Good fry day: Detail from Fish and Chip Shop, 1954, by David Hockney. Copyright: David Hockney. Photograph: Richard Schmidt

Essex Road is where it all began for Panikos Panayi, who as an infant in the 1960s enjoyed his first solid food in the local fish and chip shop. This distinguished historian, son of Greek Turkish immigrants, writes with enthusiasm about this quintessential British food in his book Fish & Chips, a History and comes up with some astonishing findings. Where better than Hackney to explore this fascinating story? The fusion of Dickensian fried potatoes for poverty stricken East Londoners with the frugal fried fish of our Jewish communities gave London a unique claim to having invented this sublime marriage of carbohydrate and protein, of comfort and deliciousness.

Back in Yorkshire in the 1940s and 50s my own passion for fish and chips grew as a yearning for forbidden fruit my middle-class granny disapproved of, and my working-class granny could not afford, such a luxury at the end of the week. She had few memories of fish and chips, but recalled how the pie man would sell them an empty pie crust with peas and gravy, after granddad had spent all the housekeeping down the pub.

A rare illicit treat at the fish and chip shop across the road from the Coop in Illingworth, on the bleak moors above Halifax, coming into the warm noisy fug of frying and chatter from the dank northern drizzle, was overwhelming. One ate standing up from twisted cones of newsprint, long before gentrification ordained dining areas with knives and forks, and sometimes even cups of tea.

Roy Shuttlebottom documented much of this, in his studies of fish and chips in Yorkshire, and an early lithograph by David Hockney from his student days in 1954 catches just the right note of bustle and comfort in his local chippie in Bradford. This print (reproduced here thanks to the generosity of David Hockney and his studio) caught my eye in an exhibition of Hockney’s work in the imposing woollen mill building in Saltaire near Bradford. It affectionately records the neat, clean and welcoming wholesome aspects of a family-run chip shop in the 1950s.

Further afield some of the best fish and chips I have ever had was from a back street, Italian-run fish and chip shop in Edinburgh, a living example of the enterprise of earlier Italian immigrants who brought to Scotland the twin delights of ice cream and fried fish. But long ago street vendors in Ancient Rome were frying up fresh fish before it went off in the heat, and this must be how our treat began, taking a highly perishable food and treating it so that it doesn’t go off but remains tasty. Frying would have been the first step, then dunking in vinegar or an acidic sauce to help it keep longer.

This tradition is not exclusively Jewish, but as Claudia Roden explains in The Book of Jewish Food it was Marrano Jews from Portugal who settled in London in the 16th century who brought this dish with them – the freshest of fresh fish, well seasoned and dipped in flour, then egg and maybe breadcrumbs, deep fried in olive oil, and eaten cold, has since then been a delicacy for Jewish communities in London. The coating seals in the juices and flavour, which tastes even better when cool. What a contrast to the crisp crackling carapace of golden batter that we enjoy hot from the fryer, when the first bite into the moist melting fish within is sadly never surpassed.

Fried potato chips are another story, first mentioned by Dickens and Mayhew in gruesome accounts of poverty in the East End, as a street snack for the poorest of the poor, then eventually the marriage made in heaven by Eastern European Joseph Malin in his establishment in Old Ford Road, Bow, apparently the first recorded fish and chip shop.

The gentrification of fish and chips began quite early. At first folks would get somewhere to sit and eat, perhaps a few tables out the back. Then it was an adjoining room with pretensions to gentility with ‘serviettes’ and ‘cruets’, which eventually morphed into designer establishments loaded with a fish restaurant menu, wine list, and dressed salads, defeating the object of a genuine ‘chippy’ where Sauvignon Blanc and char-grilled line-caught scallops most definitely do not belong.

Here in Hackney we can sample the lot, from fish and chips among battered bangers, pies, saveloys, cheap factory-farmed chicken and ribs of dubious provenance, to the establishments that offer prime quality fish and hand cut chips, cooked to perfection.

The techniques of frying are enshrined in the archives of the NFFF (National Federation of Fish Fryers) and we are enormously grateful to Panikos Panayi for monumental research he undertook therein. He reminds us that even with state of the art temperature controlled frying equipment, the judgement and intuitive skills of a good fryer are critical to a successful plateful. It’s paradoxical that the moist interior of a floured and battered fillet of haddock is just what we don’t want in a chip. The secret of Heston Blumenthal’s renowned thrice-cooked chips is the expulsion of the last whisper of moisture from the carefully selected hand cut potatoes.

That’s what makes a chip crisp and stay crisp; cooked first in water, dried by many an arcane process, fried gently, cooled, dried, then fried again more fiercely – if you are still with me – then piled up like a miniature Stonehenge, and served to rounds of applause. Soggy chips are unforgivable. I have it on good authority that the best fish and chips in the world are made in New Zealand, which is no comfort to us at all.

Chauvinistic generalisations won’t do; the jibe that down south they are too feckless and lazy to skin fish before frying is unfair. Properly scaled and prepared skin has a lovely unctuousness that contrasts well with moist fish and crisp batter; and it’s not true that north of Watford everything is fried in beef dripping. And once and for all let’s kill the pernicious idea that fish and chips are fattening. They are not.

If spuds had been around (they took their time getting here from South America) the footsore and weary Roman Army might have sampled a lot on its way up north from Bishopsgate, site of an early chippy, past the joys of Poppies in Spitalfields, a deviation to Lauriston Road and the Fish House, then back to the Great North Road pausing for a wistful sniff at Faulkner’s, stopping for a quick bite at Sutton & Sons on Stoke Newington High Street, and then on to the joys of the Jewish food stores on

Stamford Hill.

We are fortunate here in Hackney to have the history, and a wide choice of places to eat every kind of fish and chips, a living heritage, and a source of nourishment and pleasure for all.