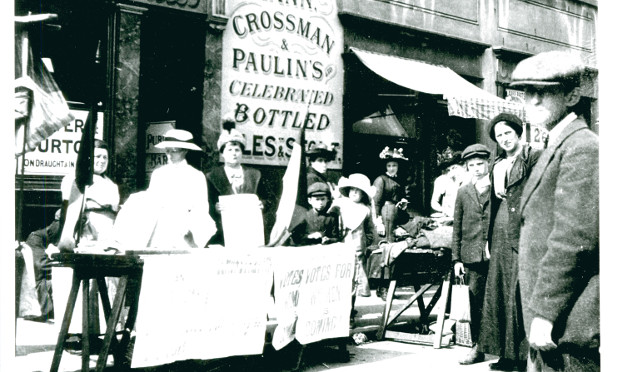

East London Suffragettes: 'more diverse than middle-class women marching around dressed in white'

In January 1914, the main Suffragette organisation in the East End, the Women’s Social and Political Union (SWPU) split in half. The eastern part re-established itself as the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS), with its own newspaper, The Women’s Dreadnaught.

Historian Sarah Jackson has marked the centenary of this event with a new book, Voices from History: East London Suffragettes, which aims to break with the image of the Suffragettes as closely associated with Westminster, West End department stores and women who could afford to march in white blouses – no mean feat when most washing was done by hand and there was enough soot in the air to give the capital its own microclimate.

Jackson and several hundred others also marked the occasion with the East London Suffragette Festival in August, a week of events with a central day of talks at Toynbee Hall on women’s history and other ‘hidden histories’ such as the role of south Asian women in the struggle to get the vote.

“We wanted to raise awareness of this quite remarkable group of campaigners, who have I think been largely forgotten, not just within the Suffragette story but also in East London as a whole,” says Jackson.

“They were a really creative, courageous group of rebels, and we thought their story would really resonate with a lot of the people in East London today, many of whom are still involved in different kinds of activism, different forms of protest, community action, all those kinds of things.”

East London was the original bridgehead in the capital for the WSPU, set up by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel. Based in Manchester, the WSPU’s first London base was set up in 1906 at the mouth of the River Lea in Canning Town.

But this Docklands HQ was gradually abandoned as the organisation moved uptown in search of wealthier and more influential members.

It was left to a second Pankhurst daughter – Sylvia – to, in Jackson’s words, “go back” to the East End, setting up in a shop in Bow in 1912. Sylvia initially met with a hostile response – “people throwing fish-heads and bits of rolled-up newspaper soaked in urine,” according to Jackson – but eventually she won people round: by the end there were reportedly over 1,000 members in Bow North alone. The eastern branch went its own way after its scope widened to include other hot topics of the early 1910s, including Irish Home Rule. Then they almost vanish from history.

“We’re lucky we have Sylvia Pankhurst’s own memoirs and correspondence – she was a middle class woman and so she wrote down a huge amount of information about what happened,” says Jackson, who built her book on the research of pioneering academic Rosemary Taylor, the original salvager of the ELFS.

“We also have The Women’s Dreadnaught; lots of women wrote for that or gave interviews if they weren’t literate; a lot of people in the East End at the time couldn’t write.

For Jackson, looking at such ‘social’ history is part of simply getting the story straight, an historiographical movement away from “wars and kings and banks”. But it also provides a link to the past for the ordinary people of today.

“There’s something extraordinary about finding out your house had a Suffragette living in it, or a 14-year- old Irish girl who worked in a match factory who went out on strike; I think it gives you a sense of connection.”

The East London Federation had a good war, organising itself to alleviate the everyday hardships its members experienced once, as Jackson puts it, “people who were already living on slender means found themselves in starvation conditions”.

The Federation lobbied for food price controls, a living wage and equal pay for women. It set up a relief programme to provide milk for poor children and opened a toy factory to employ male and female workers on an equal footing as well as a “pioneering affordable nursery”. There was an employment exchange, a clothes exchange and a place to rent children’s clothes cheaply. “This was community action,” says Jackson, “a community organising for its own survival.”

Later on, the Federation started to campaign against the war, with The Women’s Dreadnaught one of the first publications to report on shell-shock. The story goes that female suffrage was a reward for women’s work during the war. Jackson rejects this idea, pointing out that voting rights granted in 1918 were only for women over 30 and there remained a property qualification. Poor women and young women still couldn’t vote. Full female suffrage didn’t come until 1928. So why celebrate the anniversary of an organisation that could be counted as a failure?

“We need to remember that the Suffragette movement was more diverse than middle-class women marching around dressed in white,” she says, pointing out that the same view bedevils feminism today.

“It’s fantastic that you can regularly pick up a national newspaper in the UK and there’ll be a story in it about equal pay, about women’s rights, about sexual harassment, and it’s not long ago that these issues were not talked about.

“But I think there is a bit of an imbalance in the kinds of story that get picked up: getting women onto boards of blue-chip companies is a big issue but it’s important to keep the issue of the high number of women who work for below minimum wage, for instance, on the table.”

Part of doing that is not to be nostalgic about the past. “1914 and the era around that was an extraordinarily polarised time with a lot of activism – it’s easy to get caught up in this kind of heady atmosphere and think ‘what a time to be alive, all these characters, these amazing, passionate people’ – but I think it’s important to remember the context: how many girls didn’t go to school, how divided society was, the extent of poverty.”

As such, the final chapter of Jackson’s book covers women’s rights campaigns up to the present day, including the protests against moving the Women’s Library from its old home in Aldgate to the LSE in 2013.

Jackson is now writing about the Focus E15 Mothers housing occupation, looking at parallels with the East London Suffragettes of 100 years earlier. Until last month, the women occupied their former social housing block in Stratford from which they had been evicted. It’s a new and different fight, taking place only a mile or so north of the first WSPU foothold in Canning Town. History goes on.

Voices from History: East London Suffragettes by Sarah Jackson and Rosemary Taylor is published by The History Press RRP: 9.99. ISBN: 9780750960939

I know Roman road market and that particular area. Sylvia Pankhurst lived in Old Ford road I believe not far away. She lived there during her imprisonment at Holloway prison and was force fed in prison as many of the Suffragettes where the government at the time passed an act called the cat and mouse act which allowed the women to be arrested as soon as they passed the prison gates and imprisoned once again. As this article has stated many ordinary women worked tirelessly to obtain the franchise ( vote) for women to be allowed to have their voice heard in our democratic system. The Pankhursts are mostly credited as being the people who helped to do this. But we must not forget Millicent Fawcett also a leading light in the movement who thought that the Pankhurst’s especially Sylvia’s more radical ideologies where not the answer to the dilemma of votes for women she believed that more passive methods where called for and civil unrest would not help the cause. Of course the Pankhursts where well educated middle class women and women at the lower end of the social ladder like east -end women needed orators like the Pankhursts who could be their mentors. Unfortunately as time went on the Pankhursts became at logger-heads as their political views where so different.and I believe it divided them as a family. During the first world war women 30 years and over I believe it was could vote in elections but it was not until 1928 that women 21 and over where granted the right to vote. The struggle for female emancipation in this country regarding the movement had gone on for over 60 years starting from the 1800’s with Emmerline Pankhurst Sylvia’s mother.

PS if anyone has an interest in this topic regarding the votes for women in East London a good book on this subject is( in letters of Gold by Rosemary Taylor) read it myself a great read on social history and women’s struggle to be heard in our democracy.

My Grandmother’s sister (Elizabeth Mary Liston Nee Shine) was arrested 4 times, and imprisioned 4 times when she was a suffragette. She was also force-fed, horrible. I have been tracing my Family Tree for some years, and when she told me what she had gone through, I felt ill.My great-aunt Lizzie was a fighter, always telling me that a lot of her friends had died so that I could vote.

She died the night of the hurricane in 1987, she was very ill, and should have died days before. The doctors in the London Hospital seemed surprised that she held on. I thought that she knew the hurricane was coming, and wanted people to remember when she died!. We all owe a great deal deal to women like my great-aunt Lizzie.