Seeing through the spin: experts call for greater council transparency

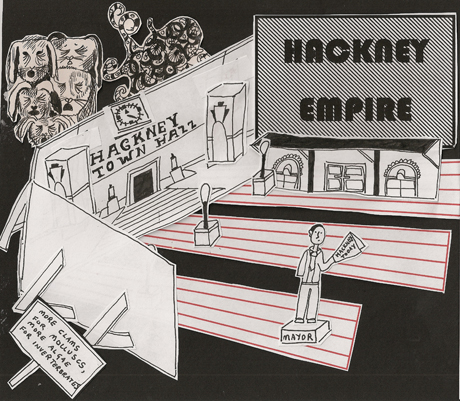

Hackney Council: maintaining the facade? Illustration: Caroline Christie and Bethany Lamont

Hackney councillors appeared worried as four leading experts on open data called for greater transparency and public access to council information at a Town Hall meeting last month.

The experts at the Overview and Scrutiny Board meeting (Tuesday 25 October) included Janet Hughes, Head of Scrutiny and Investigations at the London Assembly; Emer Coleman, Director of Digital Projects at the Greater London Authority; Jessica Crowe, former Hackney councillor and Director of the Centre for Public Scrutiny (CfPS); and Max Wind-Cowie of think-tank DEMOS.

Kicking off, all four agreed that the current provisions for data access via the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act suffered from several inadequacies, including the fact that it was request-driven, and requests had to be very specific.

They also agreed that the solution is a system of ‘open data’, where council information is freely available and accessible online to whomever wants it. This solves the problem of quality and timescale for everyone requiring information for whatever reason.

And there are further advantages. Open and transparent data can work to the council’s benefit. Releasing the data as standard practice reduces the need for cumbersome and time-consuming FOI requests.

Open data enables people requiring the information to take it, study it, adapt it to other data sets and use it how they like. It also enables the council to utilise the interpretations made by the statisticians, researchers and investigators using the data elsewhere.

Finally, it improves the quality of the data that has its own set of knock-on effects. This is because if the data is open and free it has to be high quality as it faces scrutiny. This pressures councils to produce good data (a by-product in itself of keeping clean books) that in turn yields results internally.

A cleaner, more open system inside and out makes for a more efficient and accountable local government and one that can tackle problems highlighted by the data and eventually improve public services with it.

This radical suggestion was met with a some consternation on the part of the councillors on the committee.

Labour councillor Luke Akehurst asked the experts: “What’s the criteria [for choosing which data to release]? You can’t just ‘dump’ all the data that you hold.”

The answer is simple, according to Hughes: councils should release everything unless there’s a good reason not to: “You don’t necessarily know what the value of the data is until you put it out to the public, and other people have had a look at it and come up with ideas as to the things they can do with it”.

Another objection, voiced by several members of the commission, was that in a time of straitened finances, the cost of mass data release would be exorbitant. Not so, said Coleman, who cited the London Data Store as an example of a low-cost system that had enabled publication online of large amounts of data at London level.

The key, according to Coleman, is to provide those who produce the data with a template that allows for straightforward release online once the data has been collected. She said the cost issue is “a bit of a red herring. People say it’s expensive, but it’s not.”

Cllr Robert Chapman mentioned the ‘nervousness’ in some quarters about how data would be used by newspapers and others who accessed it.

Janet Hughes countered by noting that politicians and public officials are the “worst abusers” of data, in that they “misrepresent, massage and just plain lie about statistics to support their argument”.

Her conclusion is therefore that “it is a slightly misplaced assumption that it’s alright for people inside government to have access to data, because they know how to use it, but if people outside have access to it, all hell will break loose”. The logical thing to do, in Hughes’s view, is to publish the data so that different groups have an opportunity to interpret it.

Commenting on the councillors’ concerns, Hughes said: “I understand why you are nervous about [open data]; it’s the fear of being shown up.”

But under the current inadequacies of the FOI system “people are harsh and do criticise when you can’t answer questions”. Making information more accessible could be part of the answer.

The experts on last month’s panel are backed by growing number of data revolutionaries who are pressing for change to the current FOI system.

Not surprisingly, much of the support comes from the media. The team behind the Guardian’s extensive data blog has been demonstrating what can be done with reliable data.

James Ball, a data journalist working for the Guardian’s investigations team told the Hackney Citizen of just one example of how experts breaking down data can produce common benefits.

Under the existing framework, councils have up to 20 working days to respond to an FOI request. Those putting in such requests can often end up with unsatisfactory answers.

Cllr Linda Kelly, who also attended the meeting, said that she recently put in four FOI requests but had to appeal to the FOI Commissioner who had to tell the council to give her with the requested information.

“This is transparency according to Hackney Council,” Cllr Kelly said. “If we are talking about transparency and engaging with our constituents, the idea is that when you ask for something you get it. There are no half measures.”

Related:

Here we have councillors asking what: data to release;

surely if the data concerns the public it should be released.

The recommendations may seem like statements of the bleedin’ obvious to some of us, but they’re long overdue for Hackney Council.

“I understand why you are nervous about [open data]; it’s the fear of being shown up.” – never were truer words spoken!