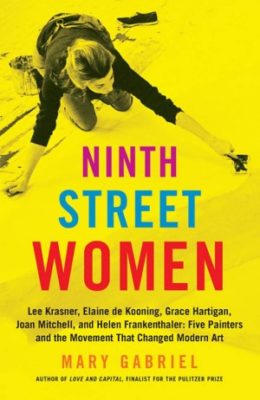

Ninth Street Women, Barbican, book presentation: ‘Rewriting male-dominated art history’

Photograph: Loomis Dean / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images

Mary Gabriel’s book is rewriting the dusty and male-dominated narrative of art history.

Focusing on the abstract art movement known as the New York School, Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art paints a revolutionary picture of the gritty, gallant, and often grim lifestyles of female artists in the mid-20th century.

In the large lecture hall of the Barbican earlier this month, the American author takes her place on the podium and thanks the audience who had come to hear her talk about the book.

She says she is glad she could celebrate the 4 July “without army tanks”, receiving a chuckle from those aware of Donald Trump’s lavish Independence Day celebrations.

She starts by explaining that she utilised the lives of five women to expose how the history of abstract art has been dominated by men.

“Women have been on the sideline of history,” Gabriel explains, and stresses the importance of remembering Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler for their influential role in developing the art world – not merely because of their gender, but because of their talent as artists within their own right.

She begins in 1929, with Lee Krasner, whose Living Colour exhibition currently fills the halls of the Barbican – read the Citizen’s review here.

Krasner’s marriage to Jackson Pollock – revered for his role in the expressionist movement – has often overshadowed her own work.

After Pollock’s death, Krasner famously said: “I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter, thank you, and a little too independent.”

Gabriel talks of Krasner’s prowess in developing her own style, which turned abstract art into a more feminine style of art, with curves, and nature-inspiring figures.

She explained: “No-one was more surprised than her when boobs appeared in her paintings.”

Krasner joined protesters in the 1960s in front of the Museum of Modern Art in New York to fight against discrimination against women artists.

Her legacy remains important today, as she set up a foundation to help struggling artists in the same position she once was.

Now, Krasner is one of the only female artists to have her own retrospective show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the same city where she fought for so many years for her place in the spotlight.

Elaine de Kooning also stood in the shadow of her partner, abstract painter Willem, and struggled to create her own identity in the post-war idea of femininity.

She grew to be fascinated with painting portraits of men, subconsciously starting a revolution in the art world; women were usually the subjects of art – drawn, erased, and painted over by the male brush.

Her most famous portrait was of President John F. Kennedy, a few months before his death.

Grace Hartigan did not want to be a mother, and fled her small-town upbringing to pursue a life of squalor and uncertainty in Manhattan’s art scene.

Her great inspiration had been Pollock’s large canvases of sporadic colours and shapes, which evoked emotion and intrigue in her.

After years attempting to create her own style distinct from those of her heroes, she would form part of the second generation of the New York School.

Her most famous series of paintings depict brides in their wedding dresses, in an abstract and distorted flurry which suggests a critique of the role of women as homemakers and child-bearers.

Gabriel explains that Hartigan suffered from severe alcoholism, and attempted suicide.

“Women experience vertigo when they soar too high,” the author notes.

Joan Mitchell’s father famously wanted her to be a boy – and her need to appease his disappointment drove her life choices.

Having taken up art himself, he told young Joan that she would never be good enough at anything because of her gender.

In her search for inspiration, she travelled to New York to gaze at De Kooning’s work in the Whitney Museum.

As money flooded into the New York art scene, Mitchell once again picked up her paintbrush and easel and moved to France in search of the “intrinsic love for painting”.

Throughout many of her relationships and marriages, painting remained the only constant.

Helen Frankenthaler’s relatives were living under the Nazi regime in Germany as Jews, and many did not survive – this haunted her work for the rest of her life.

Pieces such as Mountains and the Sea, painted in 1952, inspired the second generation of the New York School.

Frankenthaler was an innovator, and used watercolours on canvas to create new shapes and colours.

There is still ample discrimination in the art world, but acknowledging the female role in its history remains crucial to rewriting it, says Gabriel.

She ends the presentation by underlining that history takes a long time to change, but she believes that eventually these women will be remembered not because of their gender, but for their talent as artists in their own right.

Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art by Mary Gabriel is published by Little, Brown and Company, ISBN: 9780316226196.

The book is being made into a television show for Amazon Prime.

Lee Krasner: Living Colour runs until 1 September