All in a pickle: Gillian Riley turns her eye to microbes

An assortment of pickles. Photograph: Pixabay

The things we do to food to make it keep, and safe to eat, sound comfortingly medical, almost biblical: we cure and preserve, all nice and safe, but what happens when we putrefy, ferment, or pickle?

Sounds dodgy, but in fact microbes and enzymes and all kinds of bacteria are involved in the various processes.

In the past traditional ways of preserving food were developed empirically, milk could become cheese or yoghurt, meat was salted, dried or smoked, fish was dried, salted, smoked, and their entrails could be persuaded to decay and rot to give us wonderful umami rich sauces and relishes.

All these techniques involved fermentation, which didn’t just help keep stuff from going off, but added to its nutritional value, thanks to those multitudes of microbes, unseen and unknown, toiling mysteriously away within the meat, fish or cheese.

They also toil away within us – microbes, the benign inhabitants of our gut, are hard at work keeping themselves and us healthy whilst discouraging the baddy microbes.

There are millions of the good ones with different names and different job descriptions, and how to keep these busy little critters happy and productive in our colon is a nutritionist’s nightmare.

There is no one size fits all diet that will do the trick, no wonder foods or magic bullets.

We each have a different microbiome (colony of assorted bugs) within us, and the only way to help it flourish and prosper is to forget about faddy diets, according to Professor Tim Spector, cut out junk food, and eat as big a variety of ingredients as possible.

His book The Diet Myth is a beguiling account of what microbes get up to in our gut, and how and when to nurture or zap them, with accounts of rigorous testing and sometimes hilarious first hand experiences.

A shorter read is Felicity Cloake’s brilliant summary in the Guardian (26 July, 2017) 0f current views on microbes and what we eat.

Both writers tell it the way it is, leaving us to draw our own conclusions about the millions to be made for Big Pharma by its diet products, and by sweetly smiling dimpled young maidens, rich and famous from their books on the magic of clean gastronomy and newly discovered seeds and weird leaves and twigs. (Well writers for Hackney Citizen would be smiling and dimpled too if we were that smart).

Mucky Eating & Bringing home the Bacon

Here in Hackney we are fortunate in having a lovely range of things to please our microbes, either in trendy restaurants, some of which offer workshops, or at home, with ingredients available from food stores or markets all over the borough.

The best advice about feeding gut microbes is to feed ourselves, on lots of fruit and veg, plenty of fibre, fermented foods like kimchi, sauerkraut and miso, and cut down on artificially sweetened stuff, and anything with added antibiotics or preservatives and growth hormones that could upset our microbes.

We know what this does to the animals reared to give us cheap meat, and how a lot of this gets into the anonymous sludge in processed food, so I needn’t bang on about avoiding such stuff.

But the enjoyment of eating a wider range of more exciting things, and adding new ingredients to familiar ones while giving pleasure to thousands, millions, of our invisible lodgers, is its own reward.

In my very far off young days we only knew microbes as ‘germs’, nearly all baddies, and to be avoided. But I remember my mum, who had a relaxed attitude to housework, picking a jam tart up off the kitchen floor, dusting it down, handing it back to me, and quoting the local saying: “Tha has ter ate a peck o’ muck afoor tha dies.”

So rolling around the sandy floor with piglets puppies and kittens while licking the (home made of course) jam off one’s grubby fingers, was doing instinctively what vast controlled scientific experiments now confirm: that for our health and wellbeing we need those good microbes and the permissive environments they flourish in.

Excessive cleanliness can be bad news. But the flip side is that baddies can flourish as well, and I remember the misery of having to have nits and intestinal worms dealt with as a small child.

Jarred & Bottled

But what if your inner microbes demand three chip butties a day? Take them round to be re-educated at the Picklery in Dalston, Made in Hackney, or one of the many places where you can buy or learn how to make fermented food, and give them a holiday treat.

Pig out on pickles and fermented fruit and veg, and sign up for one of their courses that will keep the microbiome happy until the next binge.

Try Monty’s Deli, where delicate light and crisp homemade pickled radish, beetroot, onion, and coleslaw are made in a northern European Jewish tradition. And seek out artisanal choucroute, with all the virtues of fresh cabbage and much more.

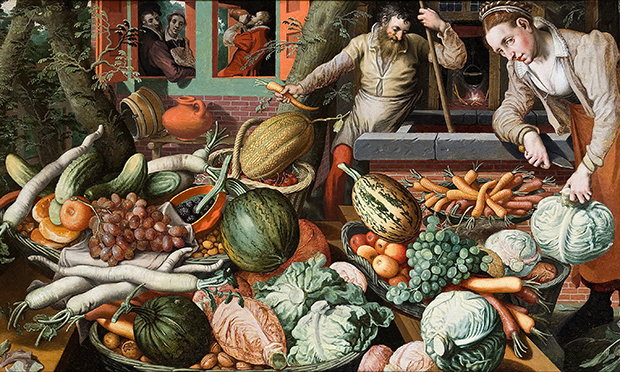

Market Scene, 1569, by Pieter Aertsen. Image: WikiCommons

This market scene (above) by Pieter Aertsen painted in 1569 is full of symbolism that delights serious art historians, what with its phallic carrots, radishes and cucumbers, and womb-like cabbages, but the range of vegetables suitable for pickling and fermenting is even more interesting for us, in search of the preserved food of the past, when getting things to keep was a matter of life and death, but for us today is a source of pleasure.

Fatherland Food

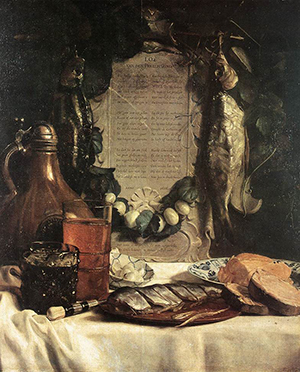

Still-Life in Praise of the Pickled Herring by Joseph de Bray. Image: WikiCommons

This painting (right) by Joseph de Bray in 1656 is a funerary monument celebrating the humble herring as one might a worthy citizen of the Dutch fatherland.

Bay leaves and herbs drape themselves in baroque curlicues among the festoons of cured fish which surround the epitaph, while the table at its foot is loaded with bread, butter, cheese and beer, the plain and simple fare that nourished the mariners and merchants who brought wealth and prosperity to seventeenth-century Holland.

The words are not pious verses, but down-to- earth doggerel, hardly printable in a family newspaper, recalling the gastric side-effects of the herring, a robust tribute to the microbes present in these staple foods and hard at work in our colons.

Professor Spector tells with glee of ‘cheese mites, transparent and understandably chubby, wriggling happily in a hardcore YouTube video’ as they munch away on the white bloom (made up of microbes) on a fine French cheese.

We too can happily munch on microbes as we shop around in Hackney for pickles and cheeses and vegetables to ferment and eat fresh.