Guerrilla Girl power! Feminist ‘masked avengers’ come to East London to take on art world

Going ape: the Guerrilla Girls. Photograph: Andrew Hindraker. Courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls

Massively influential feminist art pioneers the Guerrilla Girls once stated that “the world of artists is great, but the art world sucks”.

This conviction has shaped their project since their formation in 1980s New York, with the group challenging those in control of major museums and galleries to present and champion more work made by women and by people of colour. Their art names and shames with statistics, graphs and appeals to equality, plastered on galleries, projected onto buildings and splashed across cities on advertising billboards.

This month a new exhibition from the group opens at the Whitechapel Gallery. I sat down with two members of the group, Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz (the members use the names of deceased female artists), to discuss the new show, their recent work and the current state of the art world.

Your new work which opens at the Whitechapel Gallery is in part a revisiting of the 1986 poster ‘It’s Even Worse in Europe’. Is representation in the art world still worse in Europe than in America?

Frida Kahlo (Guerrilla Girl): Let’s just say that it’s different in Europe. Visitors to the exhibition need to come and make up their mind about that. We wanted to gather some statistical information from the mouths of the museums themselves, and then show how these European museums present themselves.

Revisited for Whitechapel Gallery exhibition: the Guerrilla Girls’ 1986 poster ‘It’s Even Worse in Europe’. Courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls

On the difference between America and Europe, I was wondering if New York in the 1980s influenced the way the group started to make work?

Kathe Kollwitz (Guerrilla Girl): We are both founding members of the Guerrilla Girls, and what we saw in the beginning was that it was almost impossible for women or artists of colour to have their work shown in commercial galleries. There was a very vibrant alternative scene, which was fantastic, but there was so much other discrimination. If you look at a poster we made in 1985 poster that lists how many museums had shows by a woman, it was one at best. Usually it was nothing. We thought that was completely ridiculous. We knew so many great artists who were women, women-identified or people of colour, and it was total discrimination.

There were demonstrations where people would walk around with picket signs, but nobody cared. The art world wants to pretend that everything is perfect, that art is a meritocracy and that the institutions and the galleries know best. We knew that wasn’t the case, and we realised that there had to be a way to talk about this that would change people’s minds and get their attention. So we started blaming one institution after another. When our posters hit the streets in May 1985, all hell broke loose. The powers that be were really pissed off.

FK: We also noticed that whilst women and people of colour were making some advances in the larger world, they were not making them in the art world. Even though it always wants to think of itself as avant-garde and ahead of it all. It even took the form of theory, because gallery owners and curators would say that women artists and artists of colour just didn’t make work that’s good enough. What that revealed was that they had a very narrow view of history. They were still dealing with a history of the art of white men, not realising that you can’t tell the history of a culture without all the voices included in the story. It was embarrassing that the art world was that far behind.

Several of the institutions that you protested against early on have now shown or acquired the work of the Guerrilla Girls. Were you ever concerned that by including your work they’re trying to dodge some of the critique within it?

KK: Absolutely. When this first started happening about ten years ago it really was a moment of truth for us. We had to sit and talk about it and think about how we were being used by these institutions. Does getting our message out to big audiences mitigate the fact that we are definitely being used by them? Our goal from the beginning was to get our message out to as many people as possible, and so we realised that we had be in the museums as well. We still love the street best though, we started on the street and still do things there.

FK: And we’re back on the street here in Whitechapel!

KK: That’s our favourite place to be. But whenever a work appears in a museum we get tons of comments and emails from people saying that they didn’t know this stuff before. So the message we’re talking about, our institutional critique and attack on the system of art (which is more and more billionaire-controlled) really needs to be there.

FK: And it’s not as though we’ve accepted every one of these invitations. We have never accepted any form of censorship from an institution. There is always a moment of truth when we present the work to the institution and they gasp! That is an important moment in itself.

Do institutions ever try to explain themselves to you?

KK: Not really. If they’ve invited us they’ve opened themselves up. They’ve invited us to critique them, and they are well-meaning people. Many people working in institutions are trying to change them. Although lot of museums think they’re doing better than they really are. In our exhibition here at the Whitechapel we have one whole section asking whether US museum practices are polluting Europe. And the answer to that was pretty much a resounding yes!

FK: In the US most of our museums are private with non-profit status, but they’re still run by art collectors. That tendency to let galleries and museums be manipulated by wealthy collectors starts in the United States. And of course, in some parts of the world, the only places you can go and see contemporary art is in an institution wholly owned, run and controlled by oligarchs.

To what extent is humour an integral part of what the Guerrilla Girls do?

KK: I think it’s a really important part. From the beginning we never wanted to do political art that says ‘this is terrible!’. We wanted to twist it around and present it in a completely different way. Humour is really great for that, because it’s disarming. You sneak into people’s minds when they laugh at something. We’ve always thought that if you laugh at something it means there’s a better chance to convert you.

Anonymity is obviously also important to the identity of the group, but what I’ve always liked is that you are present whilst anonymous, that you appear in person wearing your masks. It’s not like an internet anonymity completely removed from a physical reality.Is the face to face aspect as important as the visuals?

FK: It is, but it is tiresome. It would be fun to appear as ourselves, but I’m sure that you’re more interested in us because we’re wearing these masks. It does say something important about the world that to be taken seriously as a feminist in the art world you have to wear a gorilla mask. It’s problematic in many ways but it’s something that worked for us early on and we’re kind of stuck with it. We’re not speaking as individuals, we’re speaking as members of a subclass of angry guerrillas!

KK: It’s interesting, because people think we’re performance artists, but we’re really not. We do a very particular kind of political art that is sometimes spoken, sometimes graphic, sometime video or outdoor banners. But our masks make us performative.

FK: There’s a long American tradition of masked avengers. They’re anonymous but they have a public presence. We’re in that tradition.

During my research for this interview I came across a member of the group saying that progress is always two steps forward and one step back. Do you think that accounts for the wider climate of political regression we’re living through, with Trump, Brexit and everything else?

FK: Absolutely. The patriarchy is not going down quietly. The patriarchy is going down angry, and I think you can see that everywhere.

And having now been making such influential work over such a long period, do you see your influence in other groups or activist collectives? Are there any specific groups that you’ve noticed carrying on your work, or work like it?

KK: We do hear from a lot of people who say that we influenced them. We get all kinds of letters every year from all kinds of people, all over the world, every gender and from many, many different countries saying that they are using our work as a model for their own.

FK: I tend to think that we’re all riding on the same wave. We’re running a complaints department at Tate Modern every day from the 3–9 October, for example, and we’re inviting everyone to come complain about all kinds of issues. We’ve invited a lot of groups to come and bring all of their incredible work. It isn’t just about art, come complain about politics, social issues, economic issues, personal venting, whatever people want to come and do.

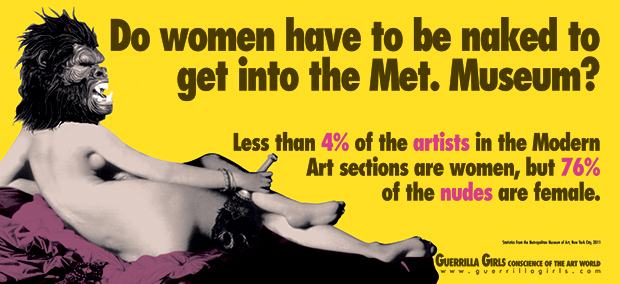

Influential: Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? poster. Courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls

What have been your biggest victories?

FK: To get other people to count for us. All of a sudden we see people in the press commenting about the representation of women and artists of colour in exhibitions. It’s great when someone else does your dirty work for you.

KK: Certainly our most influential work, the poster that asked whether women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum, really changed a lot of things. It’s a perfect example of what we do. After seeing that poster, if you really read it and it gets inside your brain, then you can’t go to a museum and look at things the same way ever again. We try every time to do something that is unforgettable in some way, and that one works.

Could you imagine a time when the Guerrilla Girls will stop making work? Perhaps because you felt the art world had changed enough so that you weren’t needed anymore?

KK: Well that’s never going to happen. There’s the whole world of culture that needs to change, including film and television, which we’ve done some work in. Firstly, I want to say that you’re talking to us today but we’re not the entire Guerrilla Girls. We’ve always been multi-generational and diverse in a lot of other ways, and we are now as well. I guess it really depends on how it goes on. It’s amazing that through incredible passion and steadfastness of argument we’ve lasted this long.

FK: I really doubt that millennia of patriarchy will be wiped by 150 years of feminism. I think we need a little bit more time to figure it all out.

Guerrilla Girls: Is it Worse in Europe? is at the Whitechapel Gallery, 77-82 Whitechapel High St, E1 7QX until 5 March.